2.7: Related Rates

When you inflate a basketball, both its volume and radius are expanding; the rates at which the radius and volume increase are related rates. In this section, we manage multiple related rates. You'll learn to determine the rate at which the basketball's radius is increasing when given another rate—the rate at which the basketball's volume expands. This topic applies the Chain Rule, which we discussed in Section 2.4, to physical phenomena.

In related rates problems, one or more quantities are changing with respect to time. When given a problem, it is important to read carefully, draw a diagram, and assign symbols. The objective is to write an equation that relates changing quantities, and then differentiate with respect to time. We use the Chain Rule because we treat each quantity—for example, height, volume, length—as a function of time.

For example, suppose \(x\) and \(Q\) are physical quantities in \(Q(x) = x^2 + 4x,\) and \(\textDeriv{x}{t} = 3.\) We use the Chain Rule to calculate \(\textDeriv{Q}{t} \col\) \[ \ba \deriv{Q}{t} &= \deriv{Q}{x} \deriv{x}{t} \nl &= (2x + 4)(3) \nl &= 6x + 12 \pd \ea \] Note that \[\deriv{Q}{t} \intEval_{x = 2} = 6(2) + 12 = 24 \pd\] The rate \(\textderiv{Q}{t} |_{x = 2}\) measures how quickly \(Q\) is changing with \(t\) when \(x = 2.\) Since we treat physical quantities as functions of time, \(t,\) we may write a physical quantity \(Q\) as \(Q(t).\) For example, we can denote a height that changes with time either as \(h\) or \(h(t);\) the difference is purely notational, and the latter form is implied.

- Understand Carefully read the problem and construct a sketch.

- Assign Give symbols to the changing quantities. For clarity, use suggestive variables—for example, \(A\) for area, \(V\) for volume, \(h\) for height. Note what you are given and what you need to find.

- Relate Write equations that relate quantities to each other. It is useful to consider what geometric shapes are formed.

- Differentiate Use the Chain Rule to differentiate the equation in Step 3 with respect to time and solve for the quantity you need.

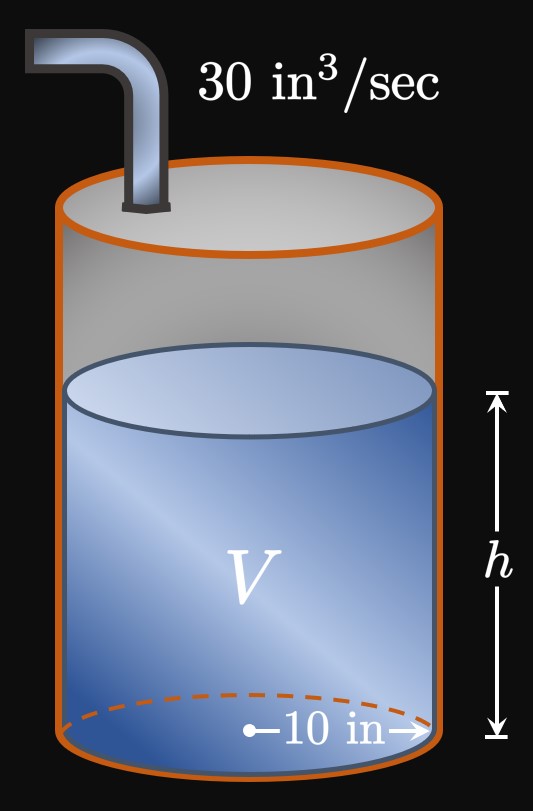

We need to construct a relationship between \(h\) and \(V.\) The volume of a cylinder of radius \(r\) and height \(h\) is \(V = \pi r^2 h.\) Here \(r = 10,\) so the water's volume is \begin{equation*} V = 100 \pi h \pd \end{equation*} We use the Chain Rule to differentiate both sides with respect to time, \(t.\) Differentiating and solving for \(\textDeriv{h}{t},\) we get \begin{align} \deriv{V}{t} &= 100 \pi \deriv{h}{t} \nonum \nl \deriv{h}{t} &= \frac{1}{100 \pi} \deriv{V}{t} \nonum \pd \end{align} Since \(\textDeriv{V}{t} = 30 \un{in}^3/\text{sec},\) we have \[\deriv{h}{t} = \frac{1}{100 \pi}(30) = \frac{3}{10 \pi} \pd\] Thus, the water level is increasing at a rate of \(3 /(10 \pi)\) \(\approx 0.095 \undiv{in}{sec}.\)

Example 1 shows a situation in which the rates are constant. In other words, \(\textDeriv{h}{t}\) does not depend on \(h,\) the depth of the water. But in other problems, rates are not constant: Sometimes we must evaluate a derivative at a given point. In these cases, we must plug in the point after computing the derivative.

TIP The best practice is to plug in numbers as the final step. In other words, after differentiating you should immediately solve for the quantity you need, before substituting values. This practice reduces the risk of committing arithmetic errors.

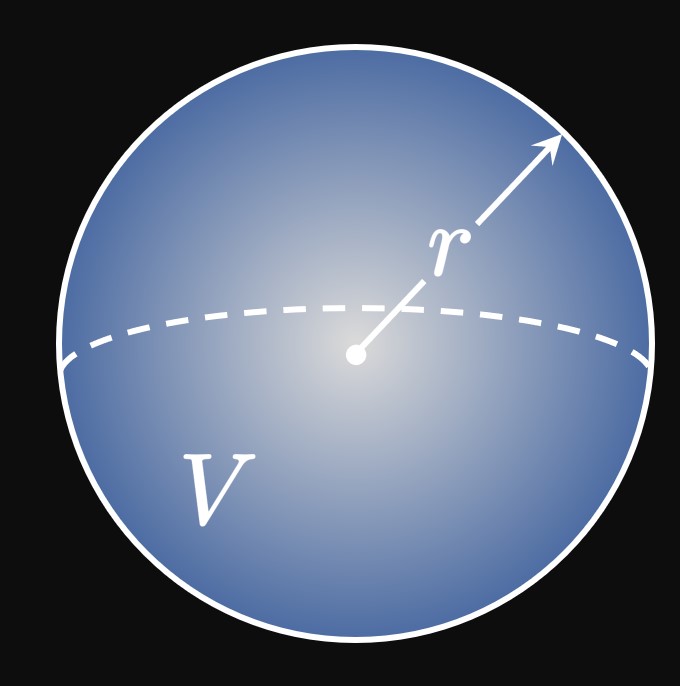

To relate \(V\) and \(r,\) we note that a sphere of radius \(r\) has volume \begin{equation} V = \tfrac{4}{3} \pi r^3 \pd \label{eq:snowball-V} \end{equation} In \(\eqRefer{eq:snowball-V}\) we differentiate both sides with respect to time by using the Chain Rule. Doing so and solving for \(\textDeriv{r}{t}\) yield \begin{align} \deriv{V}{t} &= 4 \pi r^2 \deriv{r}{t} \nonumber \nl \implies \deriv{r}{t} &= \frac{1}{4 \pi r^2} \deriv{V}{t} \pd \label{eq:snowball-dV/dt} \end{align} In \(\eqRefer{eq:snowball-dV/dt},\) we substitute \(r = 10 \un{in}\) and the given \(\textDeriv{V}{t} = -15 \un{in}^3/\un{min}\) to find \[ \deriv{r}{t} = \frac{1}{4 \pi(10)^2}(-15) = -\frac{3}{80 \pi} \pd \] Therefore, when the snowball's radius is \(10 \un{in},\) its radius is decreasing at a rate of \(3/(80 \pi) \approx 0.012 \undiv{in}{min}.\)

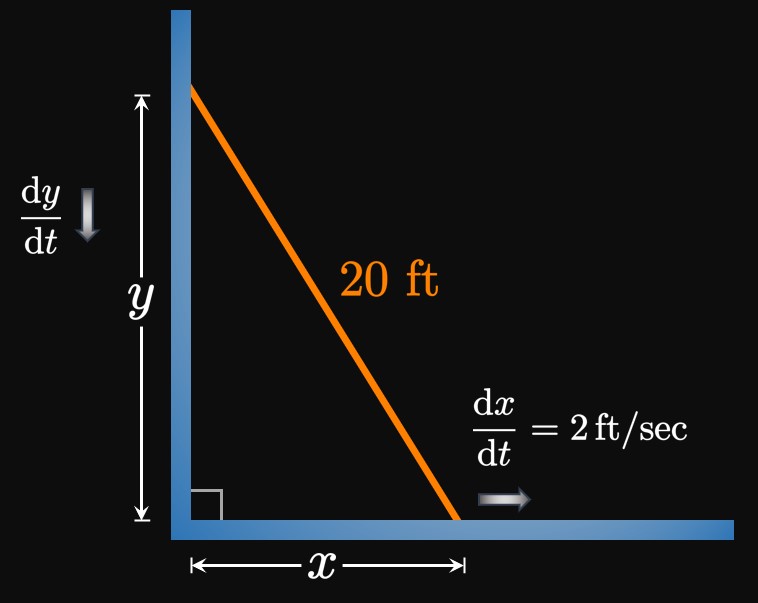

Lengths \(x\) and \(y\) form a right triangle of hypotenuse \(20 \un{ft}.\) Thus, by the Pythagorean Theorem \begin{equation} x^2 + y^2 = 20^2 \pd \label{eq:ladder-xy} \end{equation} Differentiating both sides of \(\eqRefer{eq:ladder-xy}\) with respect to time and solving for \(\textDeriv{y}{t},\) we obtain \begin{align} 2x \deriv{x}{t} + 2y \deriv{y}{t} &= 0 \nonumber \nl \implies \deriv{y}{t} &= -\frac{x}{y} \deriv{x}{t} \pd \label{eq:ladder-diff} \end{align} We want to solve for \(\textDeriv{y}{t}\) when \(x = 7 \un{ft};\) at this instant \(y = \sqrt{20^2 - 7^2} = \sqrt{351} \un{ft}\) by \(\eqRefer{eq:ladder-xy}.\) Substituting these values, along with \(\textDeriv{x}{t} = 2 \undiv{ft}{sec},\) in \(\eqRefer{eq:ladder-diff}\) then gives \[ \ba \deriv{y}{t} &= -\frac{7}{\sqrt{351}}(2) = -\frac{14}{\sqrt{351}} \pd \ea \] Therefore, when the ladder's foot is \(7 \un{ft}\) away from the wall, the top of the ladder slides down the wall at a rate of \(14/\sqrt{351}\) \(\approx 0.747 \undiv{ft}{sec}.\)

When problems involve right triangles, we want to differentiate the simplest possible form. For example, in Example 3 we chose to write the Pythagorean Theorem as \(x^2 + y^2 = 20^2\) instead of \(\sqrt{x^2 + y^2} = 20.\) Moreover, if the problem involves multiple right triangles, we want to form a relationship between their lengths by similar triangles. Therefore, it is a good idea to label angles because it is easier to spot similar triangles. The following examples demonstrate these points.

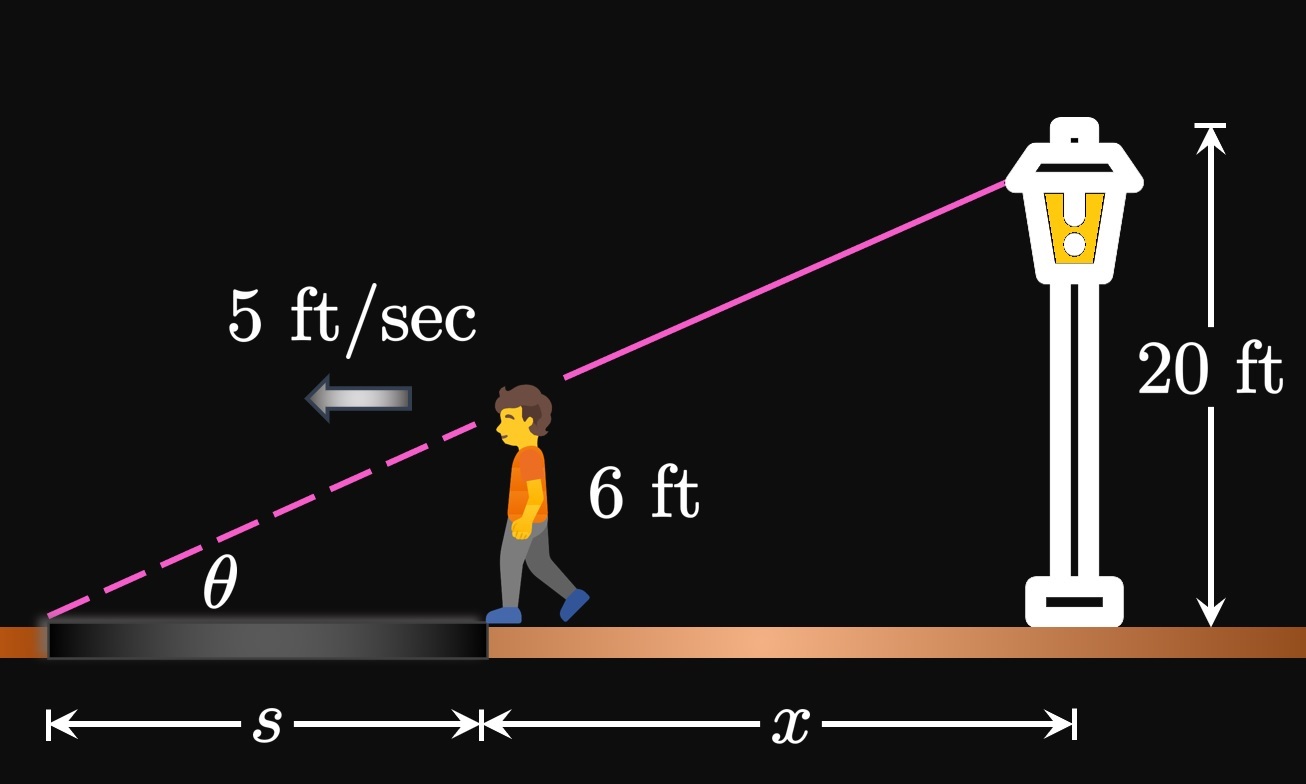

We are given that the man walks at a speed of \(5 \undiv{ft}{sec},\) so this value is \(\textDeriv{x}{t}.\) The objective is to find \(\textDeriv{s}{t}\) when \(x = 7 \un{ft}.\) We therefore need to relate \(x\) and \(s.\)

Shadow Length In Figure 4 the angle between the ground and light ray is \(\theta.\) We find two similar right triangles:

- The legs of triangle 1 are \(s\) and the man's height, \(6 \un{ft}.\)

- The legs of triangle 2 are \(s + x\) and the height of the street light, \(20 \un{ft}.\)

Tip of Shadow Let \(L\) be the length of the shadow's tip—the distance from the street light to the tip of the shadow. Then \(L = s + x;\) differentiating both sides with respect to time shows \begin{equation} \deriv{L}{t} = \deriv{s}{t} + \deriv{x}{t} \pd \label{eq:shadow-dL/dt} \end{equation} In \(\eqRefer{eq:shadow-dL/dt},\) we substitute the given \(\textDeriv{x}{t} = 5 \undiv{ft}{sec}\) as well as \(\textDeriv{s}{t} = \frac{15}{7} \undiv{ft}{sec}\) [from \(\eqRefer{eq:shadow-ds/dt-value}\)]: \[\deriv{L}{t} = \tfrac{15}{7} + 5 = \tfrac{50}{7} \pd\] Thus, the shadow's tip is growing at a rate of \(50/7\) \(\approx 7.143 \undiv{ft}{sec}.\)

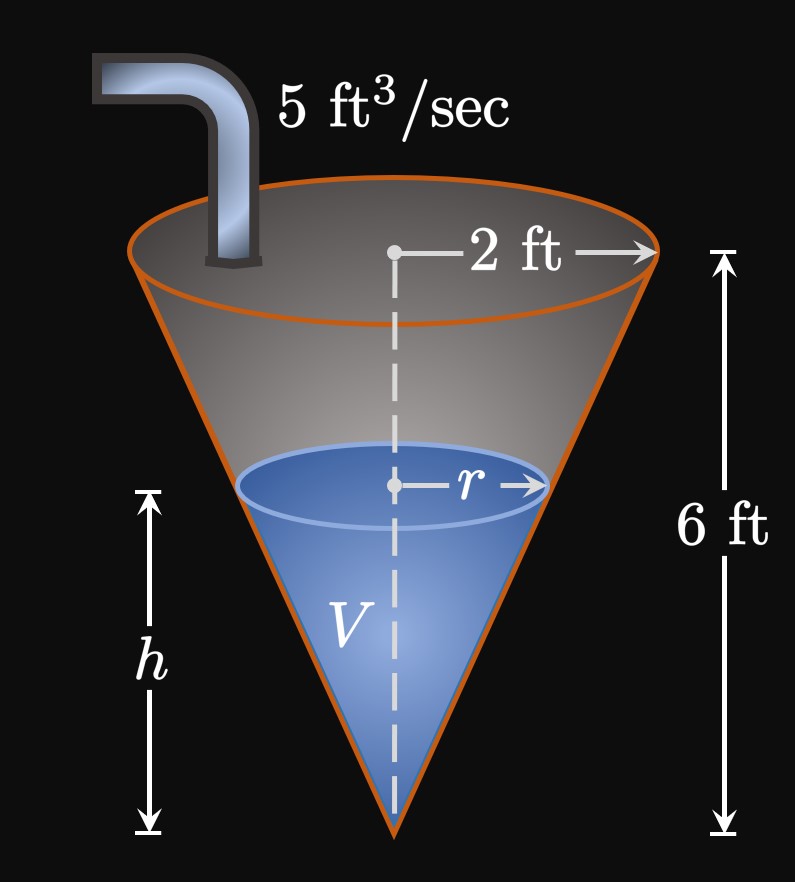

Since the entire tank has radius \(2 \un{ft}\) and height \(6 \un{ft},\) we construct a relationship using similar triangles: \[ \frac{2}{6} = \frac{r}{h} \pd \] Then \(r = \frac{2}{6}h\) \(= \frac{1}{3}h,\) which we substitute in \(\eqRefer{eq:cone-water-volume}\) to get \[V = \tfrac{1}{3} \pi \par{\tfrac{1}{3}h}^2 h = \tfrac{1}{27} \pi h^3 \pd\] Differentiating both sides with respect to time and solving for \(\textDeriv{h}{t},\) we attain \begin{align} \deriv{V}{t} &= \tfrac{1}{9} \pi h^2 \deriv{h}{t} \nonumber \nl \implies \deriv{h}{t} &= \frac{9}{\pi h^2} \deriv{V}{t} \pd \label{eq:cone-dh/dt} \end{align} In \(\eqRefer{eq:cone-dh/dt}\) we substitute \(h = 2 \un{ft}\) and the given \(\textDeriv{V}{t} = 5 \un{ft}^3/\un{sec} \col\) \[ \deriv{h}{t} = \frac{9}{\pi (2)^2}(5) = \frac{45}{4 \pi} \pd \] Thus, the water level is increasing at a rate of \(45/(4 \pi)\) \(\approx 3.581 \undiv{ft}{sec}\) when the water is \(2 \un{ft}\) deep.

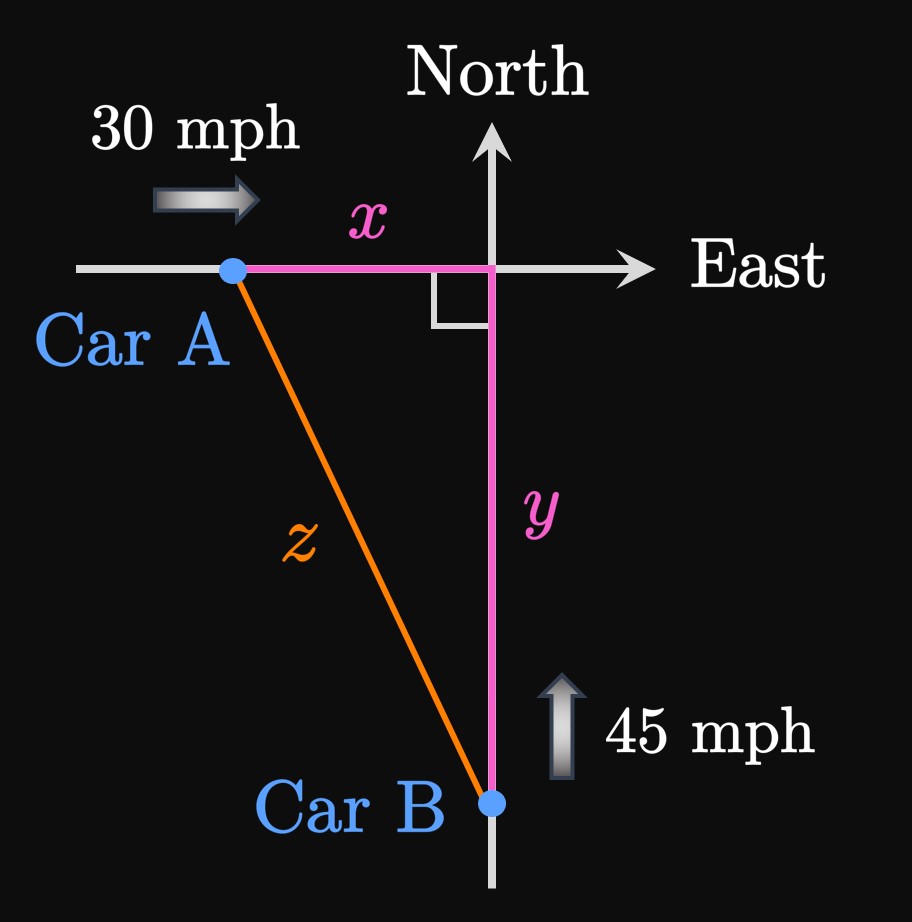

To relate \(x,\) \(y,\) and \(z\) we use the Pythagorean Theorem: \begin{equation} z^2 = x^2 + y^2 \pd \label{eq:cars-pythag} \end{equation} All three quantities vary with time, so we need the Chain Rule to differentiate \(\eqRefer{eq:cars-pythag}\) with respect to time. Differentiating and solving for \(\textDeriv{z}{t}\) produce \begin{align} 2z \deriv{z}{t} &= 2x \deriv{x}{t} + 2y \deriv{y}{t} \nonumber \nl \implies \deriv{z}{t} &= \frac{1}{z} \left[x \deriv{x}{t} + y \deriv{y}{t}\right] \pd \label{eq:cars-pythag-diff} \end{align}

Now we substitute values: When \(x = 6 \un{mi}\) and \(y = 8 \un{mi},\) \(\eqRefer{eq:cars-pythag}\) gives \(z = \sqrt{6^2 + 8^2} = 10 \un{mi}.\) Substituting these quantities, along with \(\textDeriv{x}{t} = -30 \undiv{mi}{hr}\) and \(\textDeriv{y}{t} = -45 \undiv{mi}{hr},\) in \(\eqRefer{eq:cars-pythag-diff}\) gives \[\deriv{z}{t} = \tfrac{1}{10} \left[(6)(-30) + (8)(-45) \right] = -54 \pd\] Thus, the distance between cars A and B is decreasing at a rate of \(54 \undiv{mi}{hr}\) when car A is \(6 \un{mi}\) west of the intersection and car B is \(8 \un{mi}\) south of the intersection.

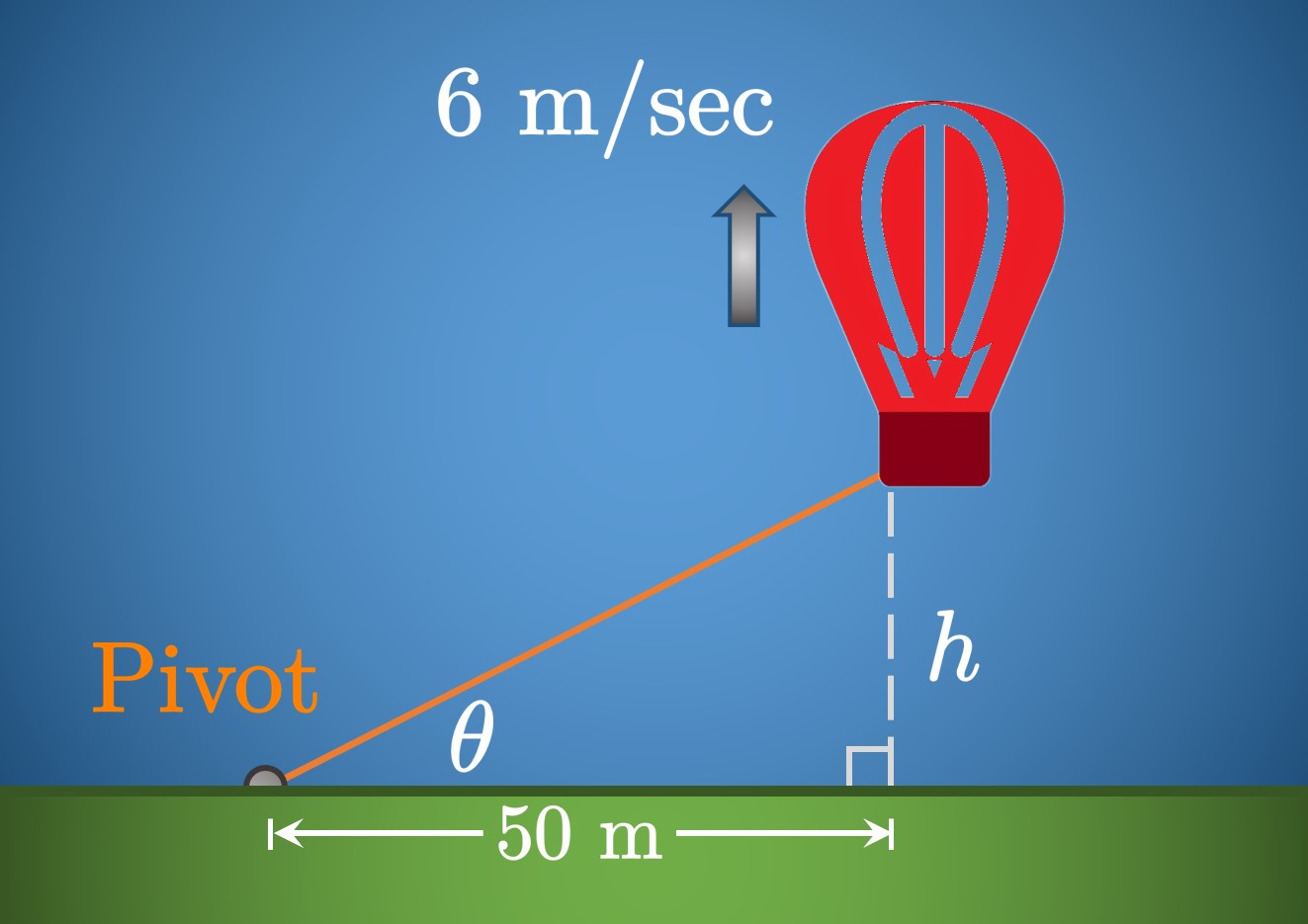

Drawing a sketch (Figure 7), we let \(h\) be the balloon's altitude. The angle \(\theta\) is formed between the cable and ground, and the pivot point is a fixed \(50 \un{m}\) away from the balloon's ground shadow. The balloon ascends at a speed of \(6 \undiv{m}{sec},\) so this rate is \(\textDeriv{h}{t}.\) We want to find \(\textDeriv{\theta}{t}\) when \(h = 40 \un{m};\) this rate should be positive because the angle of elevation is increasing as the balloon rises.

We relate \(\theta\) to \(h\) using

\begin{equation}

\tan \theta = \frac{h}{50} \pd \label{eq:balloon-tan-theta}

\end{equation}

Differentiating both sides of \(\eqRefer{eq:balloon-tan-theta}\) with respect to time,

we obtain

\begin{equation}

\sec^2 \theta \deriv{\theta}{t} = \frac{1}{50} \deriv{h}{t} \pd \label{eq:balloon-diff}

\end{equation}

For simplicity we express \(\eqref{eq:balloon-diff}\) solely in terms of \(h \col \)

Since \(\sec^2 \theta = \tan^2 \theta + 1\) and \(\tan \theta = h/50\)

In problems with related rates, multiple rates are simultaneously changing. The following steps will guide you in solving these problems:

- Understand Carefully read the problem and construct a sketch.

- Assign Give symbols to the changing quantities. For clarity, use suggestive variables—for example, \(A\) for area, \(V\) for volume, \(h\) for height. Note what you are given and what you need to find.

- Relate Write equations that relate quantities to each other. It is useful to consider what geometric shapes are formed.

- Differentiate Use the Chain Rule to differentiate the equation in Step 3 with respect to time and solve for the quantity you need.