6.5: Improper Integrals

Up to this point, we have covered integrals that featured finite bounds or were well defined on the interval of integration. But in this section, we discuss integrals that represent areas over infinite intervals or with infinite discontinuities. We call these integrals improper integrals, examples of which are \[\int_1^\infty \frac{1}{x^2} \di x \and \int_{-1}^0 \frac{1}{x^2} \di x \pd\] We discuss the following topics:

Type I Improper Integrals

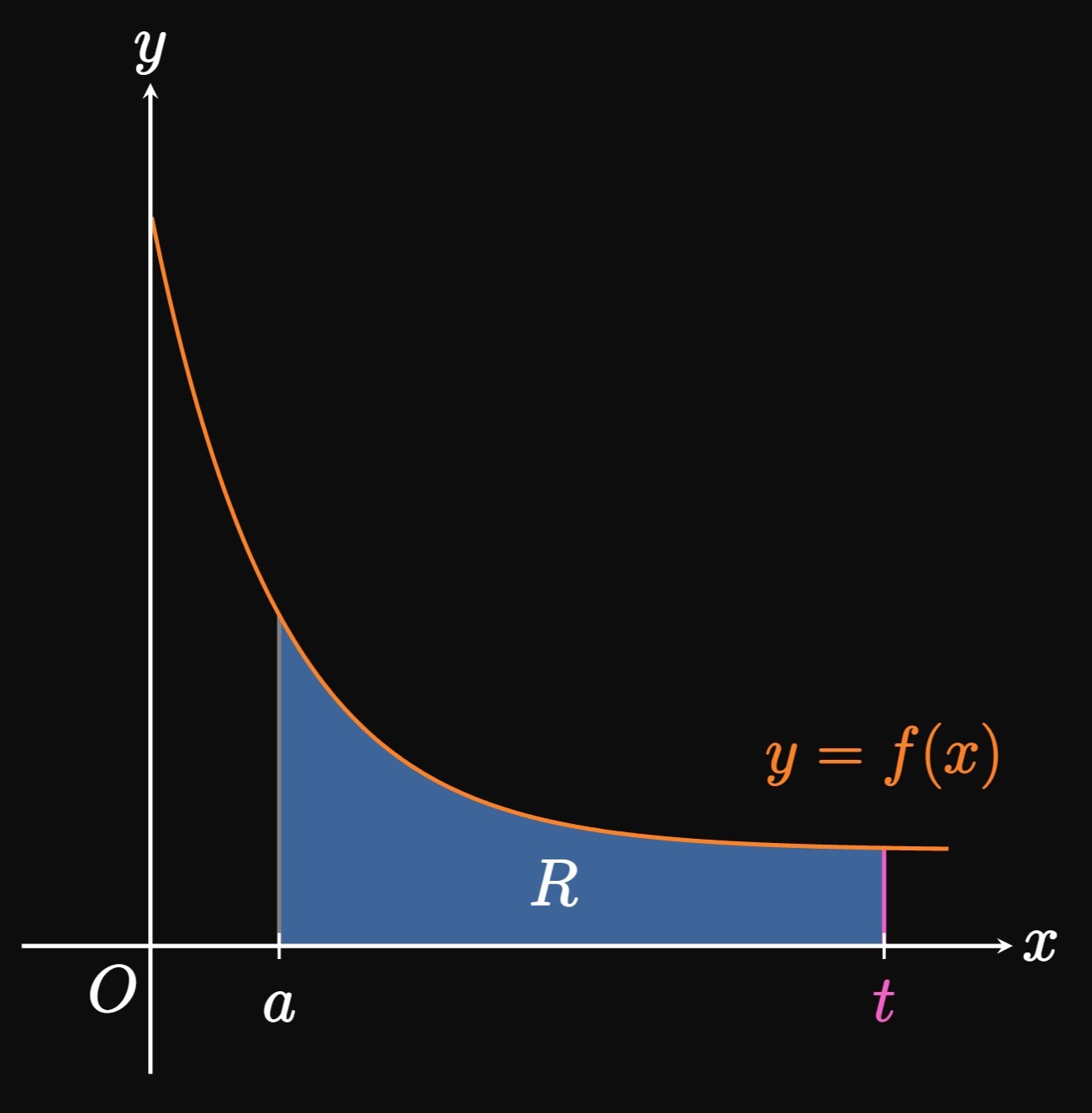

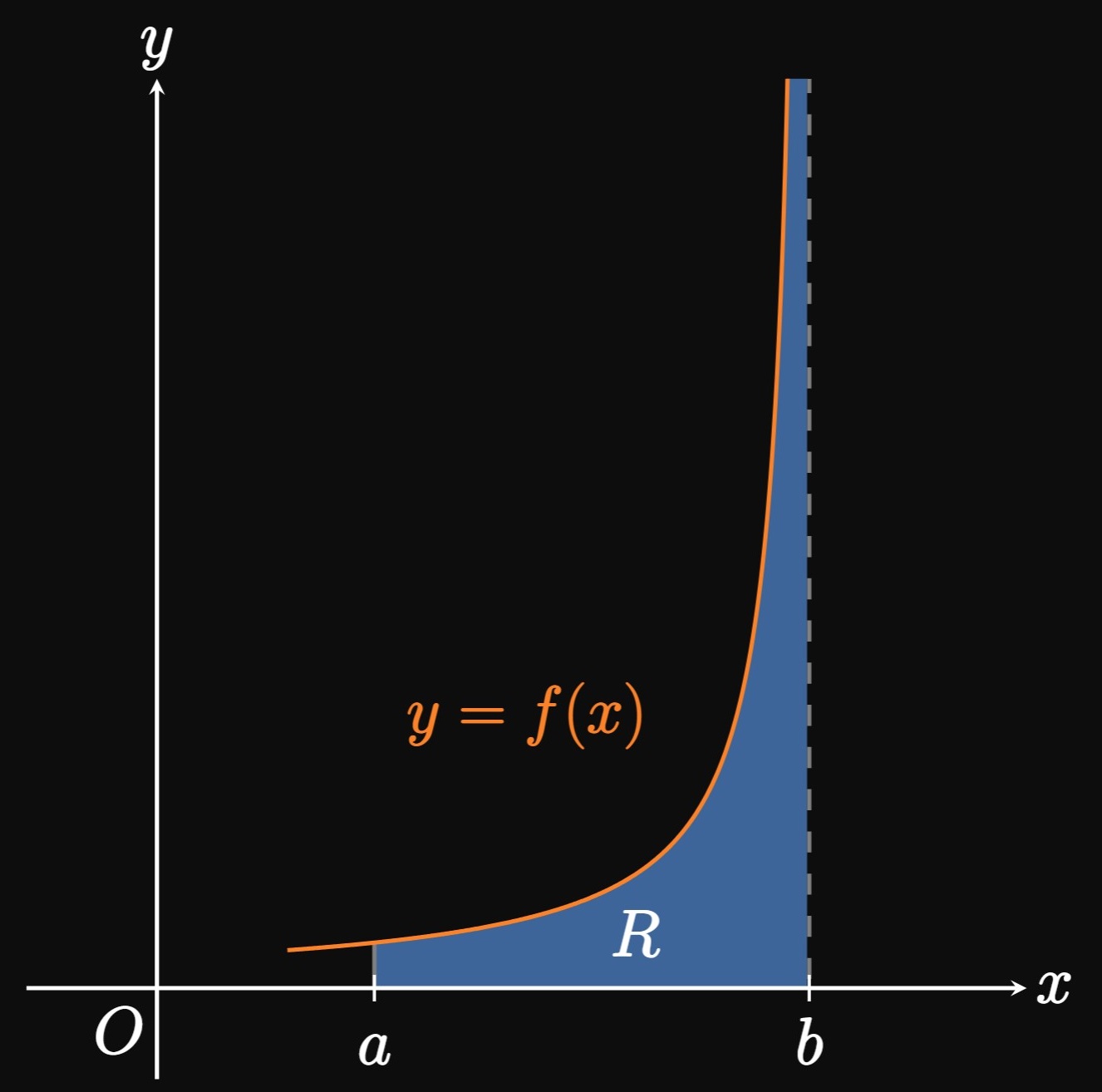

A Type I improper integral has one or more infinite limits of integration, such as \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x.\) In other words, we integrate \(f\) over the infinite interval \([a, \infty).\) But what does the upper bound of \(\infty\) mean? Let's first consider the proper integral \(\int_a^t f(x) \di x.\) For the case \(f(x) \geq 0\) and \(t \gt a,\) the integral represents the area under the graph \(y = f(x)\) from \(x = a\) to \(x = t.\) (See Figure 1.) As \(t\) grows, the line \(x = t\) shifts farther to the right, thus expanding region \(R.\) If \(t\) increases without bound, then the interval of integration becomes unbounded and so \(R\) represents an infinite region. Consequently, we write \[\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to \infty} \int_a^t f(x) \di x \pd\] To evaluate this integral, we first evaluate \(\int_a^t f(x) \di x\) and then take the limit of the resulting expression as \(t \to \infty.\) If the limit exists, then we say \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) converges (or is convergent); otherwise, the improper integral diverges (or is divergent). For the special case \(f(x) \geq 0,\) \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) converges if the region \(R\) has a finite area. By similar logic, we define two other forms of Type I improper integrals using limits of integrals over finite intervals, as follows.

- If \(\int_a^t f(x) \di x\) exists for all \(t \geq a,\) then \[\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to \infty} \int_a^t f(x) \di x \pd\]

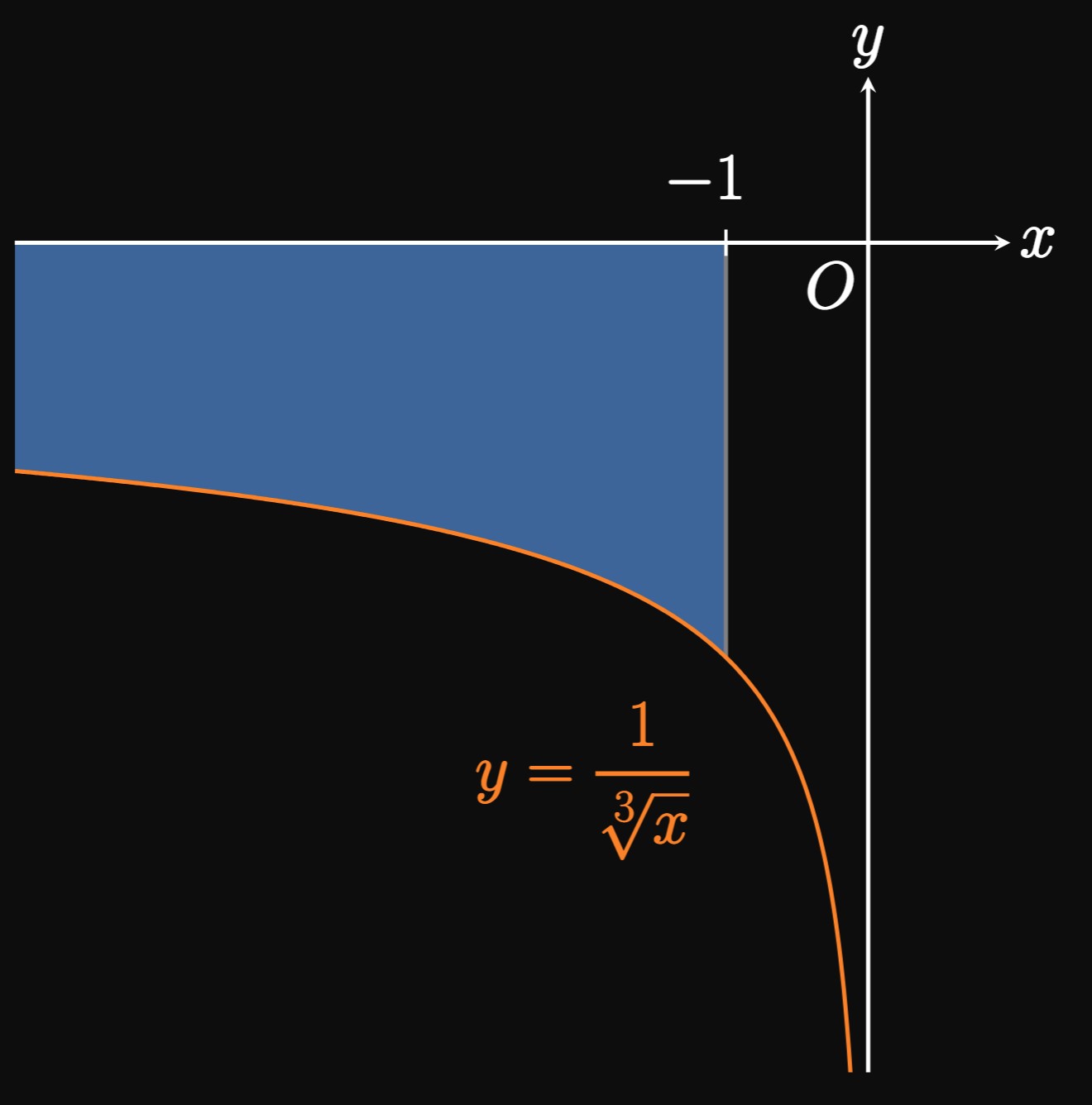

- If \(\int_{t}^b f(x) \di x\) exists for all \(t \leq b,\) then \[\int_{-\infty}^b f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to -\infty} \int_t^b f(x) \di x \pd\]

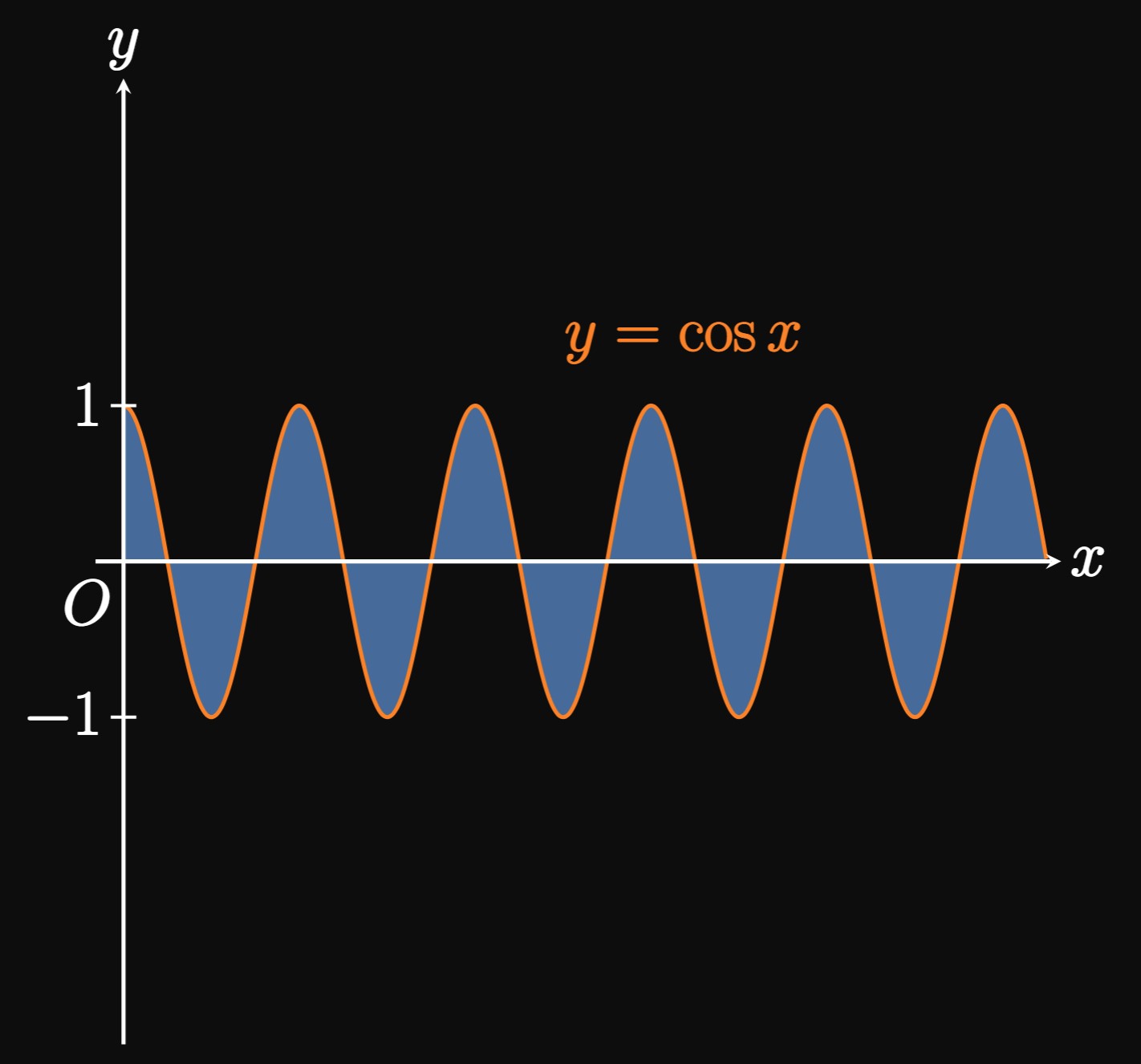

- If \(c\) is any real number, and \(\int_{-\infty}^c f(x) \di x\) and \(\int_c^\infty f(x) \di x\) both converge, then \[\int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x) \di x = \int_{-\infty}^c f(x) \di x + \int_c^\infty f(x) \di x \pd\] If either \(\int_{-\infty}^c f(x) \di x\) or \(\int_c^\infty f(x) \di x\) diverges, then \(\int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x) \di x\) diverges.

\(p\)-Integrals

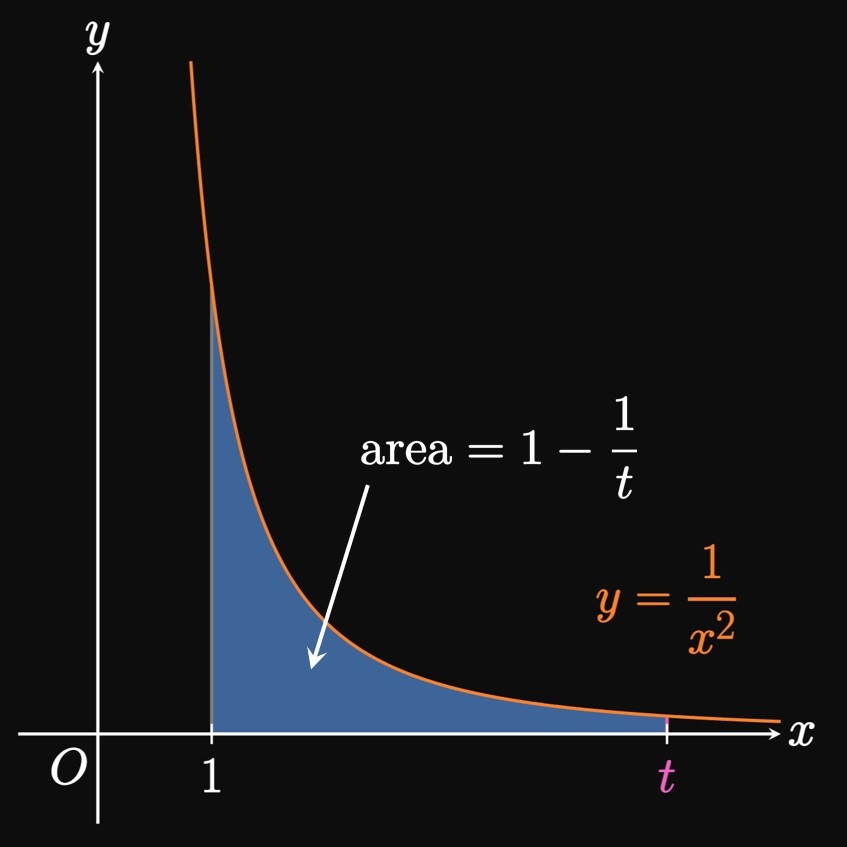

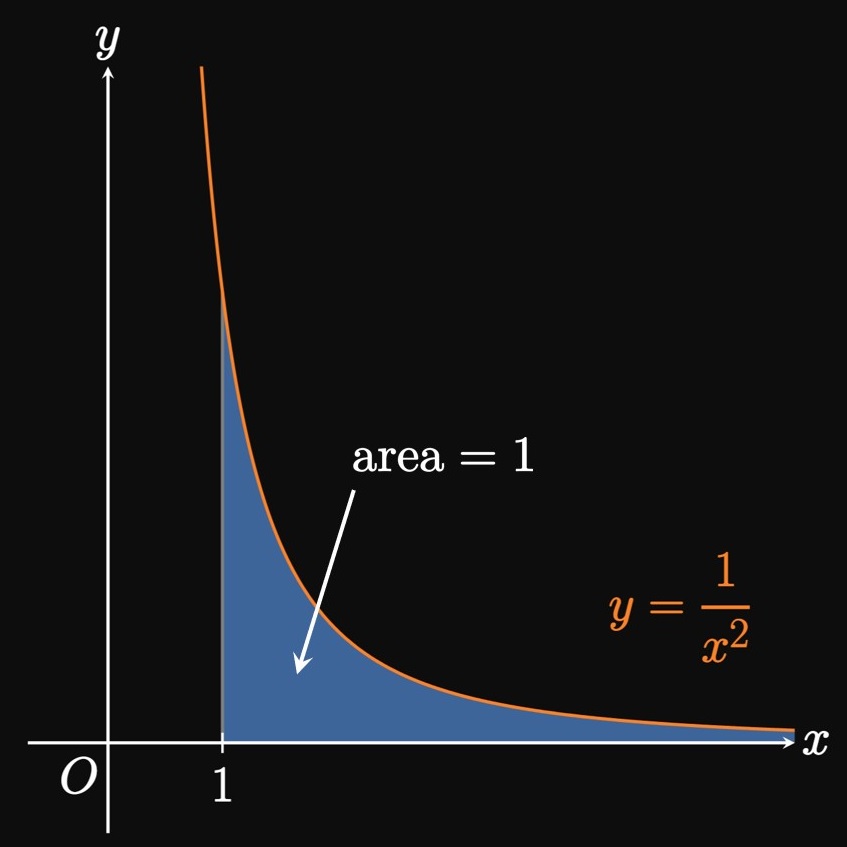

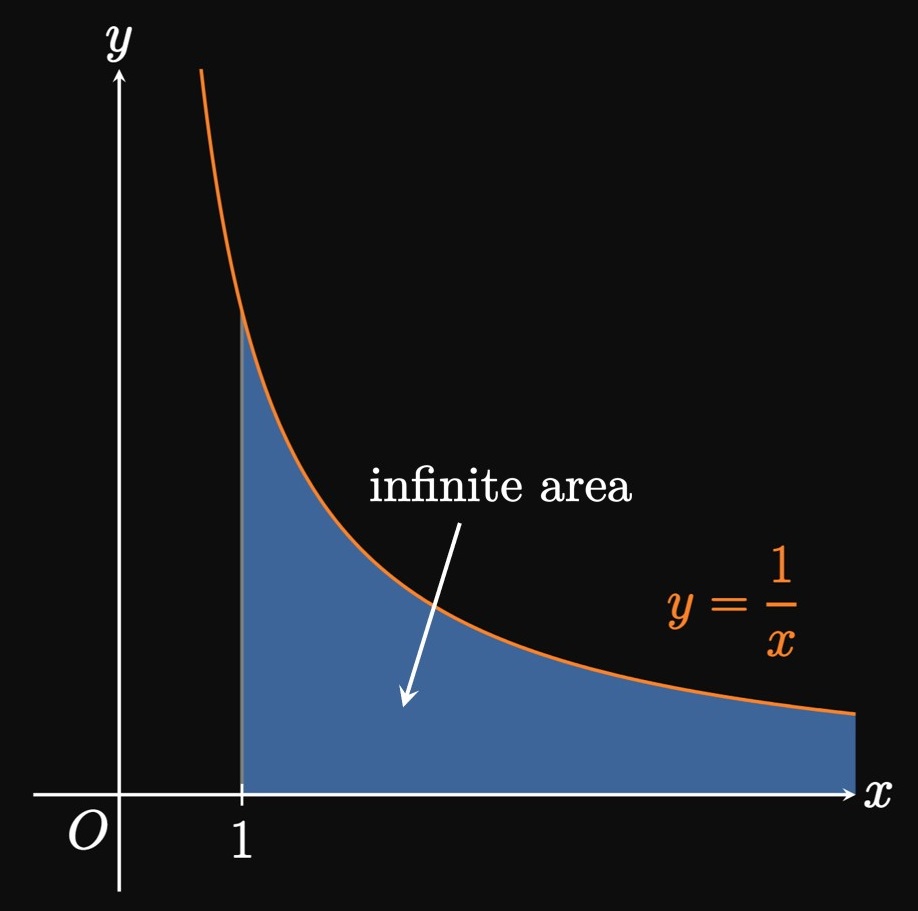

We have discovered a paradoxical fact: \(\int_1^\infty \dd x/x^2\) converges (Example 1), while the similar \(\int_1^\infty \dd x/x\) diverges (Example 2). How can we generalize the convergence or divergence of the family of integrals \(\int_1^\infty \dd x/x^p,\) called a \(\bf p\)-integral? As previously established, the integral converges for \(p = 2\) and diverges for \(p = 1.\) Generally, for \(p \ne 1\) we see \begin{align} \int_1^\infty \frac{1}{x^p} \di x &= \lim_{t \to \infty} \par{\frac{x^{1 - p}}{1 - p}} \intEval_1^t \nonum \nl &= \lim_{t \to \infty} \par{\frac{t^{1 - p}}{1 - p}} - \frac{1}{1 - p} \pd \label{eq:p-int-lim} \end{align} If \(p \lt 1,\) then \(1 - p\) is positive and so \(t^{1 - p} \to \infty\) as \(t \to \infty.\) Then the expression in \(\eqref{eq:p-int-lim}\) becomes \(\infty,\) so \(\int_1^\infty \dd x/x^p\) diverges for \(p \lt 1.\) Conversely, if \(p \gt 1\) then \(1 - p\) is negative, so \(t^{1 - p} \to 0\) as \(t \to \infty.\) As a result, \(\eqref{eq:p-int-lim}\) becomes \[ 0 -\frac{1}{1 - p} = \frac{1}{p - 1} \cma \] a finite number, so \(\int_1^\infty \dd x/x^p\) converges. Consequently, the \(p\)-integral \(\int_1^\infty \dd x/x^p\) diverges for \(p \leq 1\) and converges for \(p \gt 1.\)

Type II Improper Integrals

In Figure 6 the graph of \(y = f(x)\) has a vertical asymptote at \(x = b.\) The region \(R\) is infinite, so the integral \(\int_a^b f(x) \di x\) is improper. Using a similar procedure from Type I integrals, we imagine moving a vertical line \(x = t,\) \(a \lt t \lt b,\) closer and closer to the vertical asymptote at \(x = b.\) During this procedure, the area \(\int_a^t f(x) \di x\) better approximates the area of region \(R.\) We therefore define \[\int_a^b f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to b^-} \int_a^t f(x) \di x \pd\] This definition applies to any function \(f\) that is continuous on \([a, b),\) not just positive functions. This integral is an example of a Type II improper integral, in which the integrand has an infinite discontinuity between the limits of integration. We define two other forms of Type II improper integrals, as shown below.

- If \(f\) is continuous on \([a, b)\) and discontinuous at \(b,\) then \[\int_a^b f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to b^-} \int_a^t f(x) \di x \pd\]

- If \(f\) is continuous over \((a, b]\) and discontinuous at \(a,\) then \[\int_a^b f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to a^+} \int_t^b f(x) \di x \pd\]

- If \(f\) has a discontinuity at \(x = c,\) where \(a \lt c \lt b,\) and \(\int_a^c f(x) \di x\) and \(\int_c^b f(x) \di x\) are both convergent, then \[\int_a^b f(x) \di x = \int_a^c f(x) \di x + \int_c^b f(x) \di x \pd\] If either \(\int_a^c f(x) \di x\) or \(\int_c^b f(x) \di x\) diverges, then \(\int_a^b f(x) \di x\) also diverges.

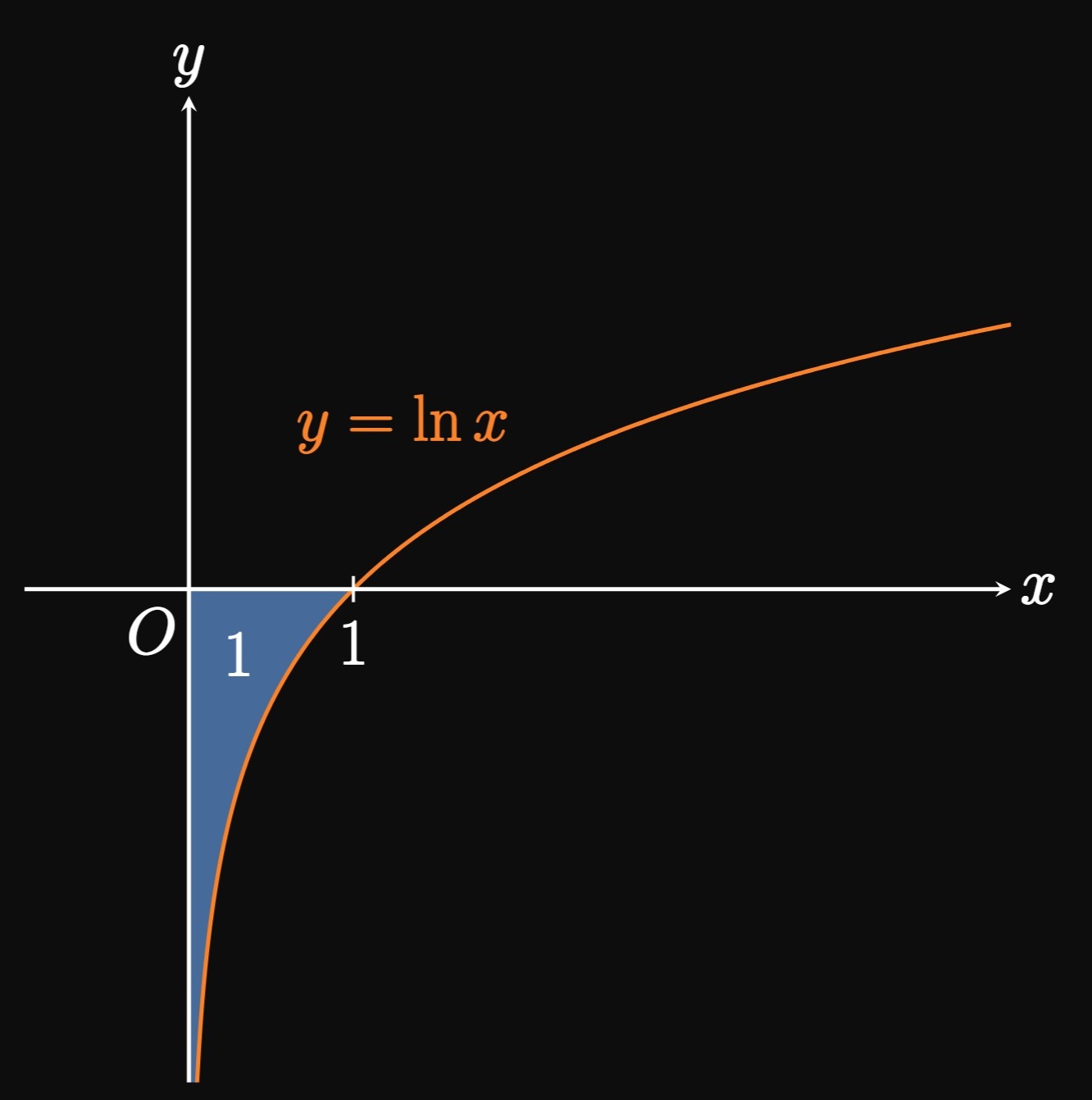

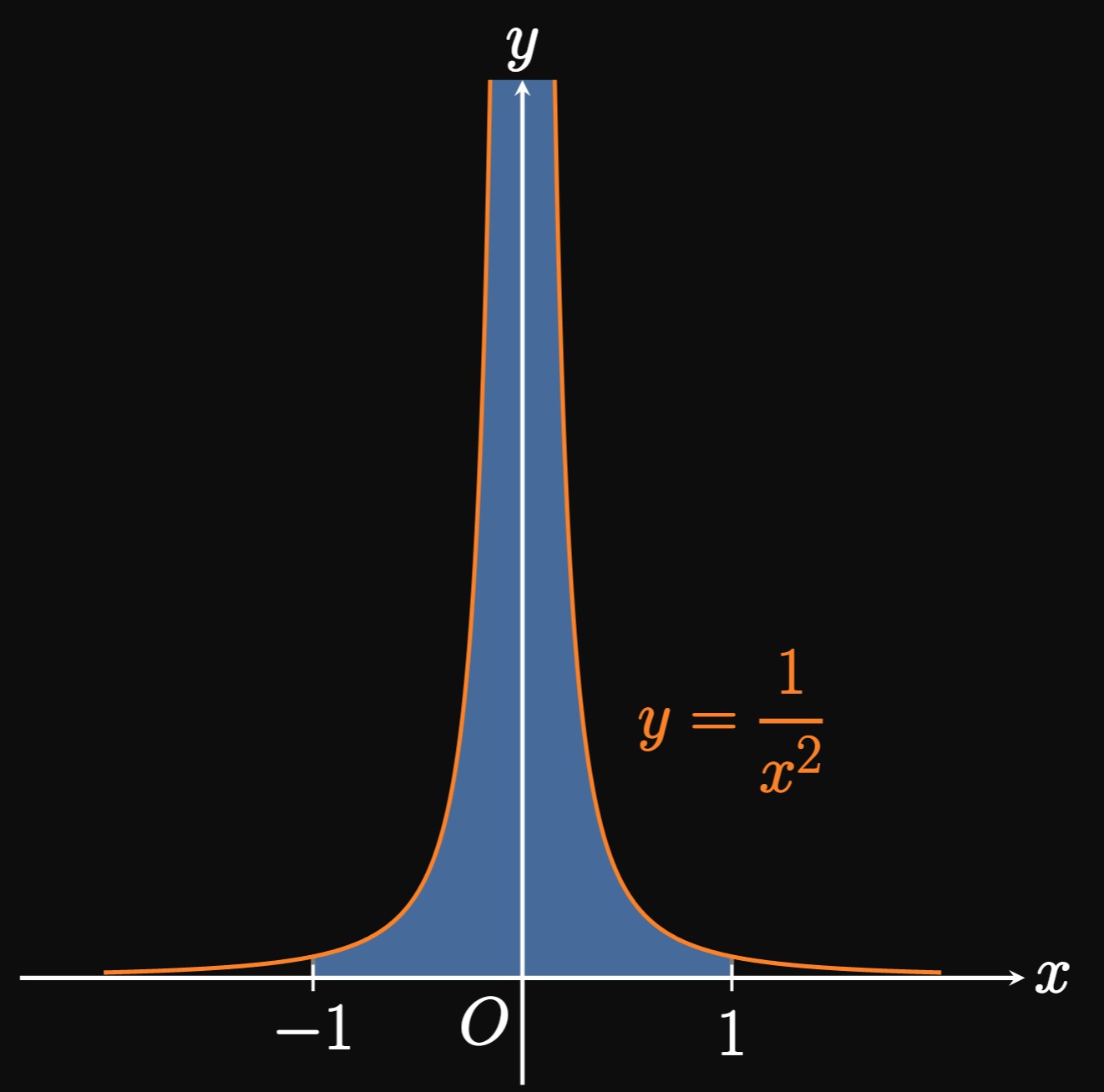

Example 7 demonstrates a common trap—Type II improper integrals are not obvious to identify. From this point on, you must determine whether a definite integral is improper. For example, it is tempting to write \[\int_{-1}^1 \frac{1}{x^2} \di x = - \frac{1}{x} \intEval_{-1}^1 = -2 \cma\] but this result is nonsensical because \(1/x^2\) is strictly positive. It turns out that Part II of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus requires the integrand to be continuous over \([-1, 1],\) so it cannot be applied to \(\int_{-1}^1 \dd x/x^2.\)

Comparison Testing

The improper integral \(\int_1^\infty \dd x/x^4\) converges because it is a \(p\)-integral with \(p = 4 \gt 1.\) But does the similar-looking integral \(\int_1^\infty \dd x/(x^4 + 1)\) converge or diverge? Evaluating the integral is very difficult, so another viable option is needed to attain a conclusion—a comparison to another integral.

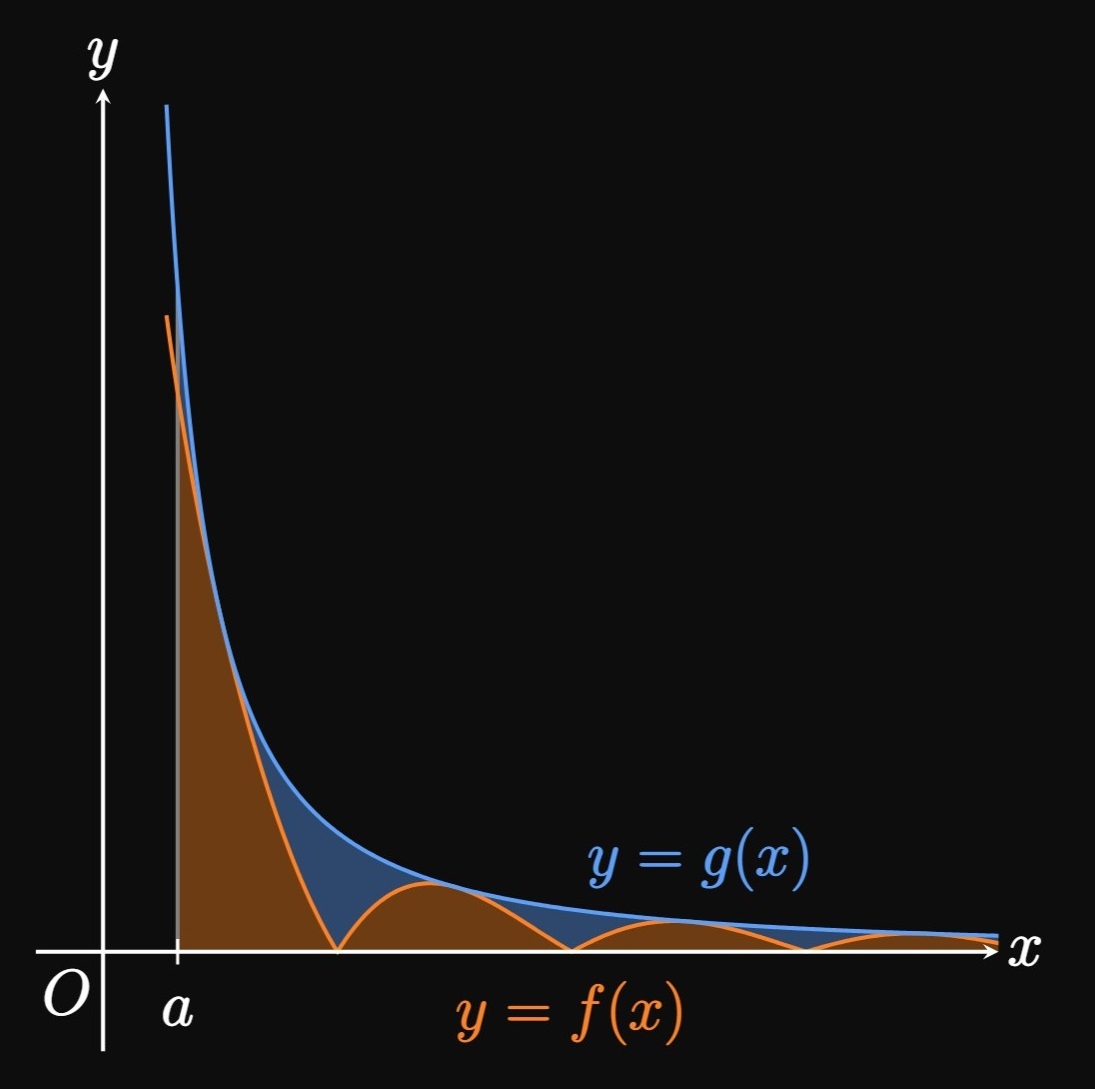

To introduce this idea, let \(f\) and \(g\) be continuous functions on \([a, \infty).\)

If

\[0 \leq f(x) \leq g(x)\]

and \(\int_a^\infty g(x) \di x\) converges,

then \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) also converges because \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) is bounded between two finite numbers.

For the special case where \(f\) and \(g\) are positive,

the area under \(y = f(x)\) is less than the area under \(y = g(x),\)

so \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) is finite.

(See Figure 9.)

Informally, if the larger

integral converges, then the smaller

integral also converges.

By contrast, if

\[0 \leq g(x) \leq f(x)\]

and \(\int_a^\infty g(x) \di x\) diverges, then \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) also diverges.

Informally, if the smaller

integral diverges, then the larger

integral also diverges.

We summarize these facts below for Type I improper integrals.

- If \(0 \leq f(x) \leq g(x)\) on \([a, \infty)\) and \(\int_a^\infty g(x) \di x\) converges, then \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) also converges.

- If \(0 \leq g(x) \leq f(x)\) on \([a, \infty)\) and \(\int_a^\infty g(x) \di x\) diverges, then \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) also diverges.

Type I Improper Integrals An improper integral represents an infinite region. A Type I improper integral has one or more infinite limits of integration. To evaluate one, we replace the infinite bound of integration with some variable \(t\) and take the infinite limit. An improper integral converges if its corresponding limit exists; otherwise, it diverges.

- If \(\int_a^t f(x) \di x\) exists for all \(t \geq a,\) then \[\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to \infty} \int_a^t f(x) \di x \pd\]

- If \(\int_{t}^b f(x) \di x\) exists for all \(t \leq b,\) then \[\int_{-\infty}^b f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to -\infty} \int_t^b f(x) \di x \pd\]

- If \(c\) is any real number, and \(\int_{-\infty}^c f(x) \di x\) and \(\int_c^\infty f(x) \di x\) both converge, then \[\int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x) \di x = \int_{-\infty}^c f(x) \di x + \int_c^\infty f(x) \di x \pd\] If either \(\int_{-\infty}^c f(x) \di x\) or \(\int_c^\infty f(x) \di x\) diverges, then \(\int_{-\infty}^\infty f(x) \di x\) diverges.

\(p\)-Integrals A \(\bf p\)-integral is a Type I improper integral in the form \(\int_1^\infty \dd x/x^p.\) The integral converges if \(p \gt 1\) and diverges if \(p \leq 1.\)

Type II Improper Integrals A Type II improper integral represents a region that contains an infinite discontinuity.

- If \(f\) is continuous on \([a, b)\) and discontinuous at \(b,\) then \[\int_a^b f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to b^-} \int_a^t f(x) \di x \pd\]

- If \(f\) is continuous over \((a, b]\) and discontinuous at \(a,\) then \[\int_a^b f(x) \di x = \lim_{t \to a^+} \int_t^b f(x) \di x \pd\]

- If \(f\) has a discontinuity at \(x = c,\) where \(a \lt c \lt b,\) and \(\int_a^c f(x) \di x\) and \(\int_c^b f(x) \di x\) are both convergent, then \[\int_a^b f(x) \di x = \int_a^c f(x) \di x + \int_c^b f(x) \di x \pd\] If either \(\int_a^c f(x) \di x\) or \(\int_c^b f(x) \di x\) diverges, then \(\int_a^b f(x) \di x\) also diverges.

It is very easy to attain incorrect results for definite integrals if you do not realize they are improper. From now on, you must determine whether a definite integral is improper.

Comparison Testing We can conclude whether an improper integral converges or diverges by comparing it to another improper integral whose convergence or divergence is known.

- If \(0 \leq f(x) \leq g(x)\) and \(\int_a^\infty g(x) \di x\) converges, then \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) also converges.

- If \(0 \leq g(x) \leq f(x)\) and \(\int_a^\infty g(x) \di x\) diverges, then \(\int_a^\infty f(x) \di x\) also diverges.

Comparison testing is useful when an integral cannot be directly evaluated.