3.6: Optimization

Optimization is the process by which a quantity of interest is maximized or minimized. It is a mathematical procedure that applies absolute extrema, which we investigated in Section 3.1, to real-world problems. The emphasis on efficiency in the everyday world cultivates the need for optimization in a wide range of applications, including geometry, finance, and science. Examples of optimization problems include maximizing volume, minimizing surface area, minimizing materials used, minimizing time, and maximizing profit. In this section, we explore the strategy to solve these problems and see their diverse uses.

Often, the most difficult step is understanding the problem and setting up equations. Let's introduce some general problem-solving steps for optimization problems.

- Understand Understand the situation by drawing diagrams and testing various possibilities.

- Notation Assign a variable—say, \(Q\)—to the quantity to maximize or minimize. Introduce notation by assigning algebraic quantities to unknown values. It is helpful to use suggestive variables, such as \(A\) for area, \(d\) for distance, and \(L\) for length.

- Express Express \(Q\) in terms of one variable—say, \(x\)—to obtain \(Q(x).\)

- Minimize or Maximize Use calculus to find the absolute minimum or maximum of \(Q(x).\) Find the critical numbers of \(Q\) and consider the endpoints of the domain in context.

The First-Derivative Test and the Second-Derivative Test (Section 3.3) allow us to determine whether a critical number corresponds to a relative minimum or maximum. To locate the absolute minimum or maximum, first establish the domain of \(Q.\) For example, if \(Q(x)\) represents area, then no side length \(x\) can result in a negative value of \(Q.\) Afterward, consider the endpoints or end behavior of the domain. Analyze extreme cases: What happens to \(Q(x)\) if \(x\) is made as small as possible? What happens if \(x\) is made as large as possible?

- \(f\) has a relative minimum at \(c\) if \(f'\) changes sign from negative to positive at \(c.\)

- \(f\) has a relative maximum at \(c\) if \(f'\) changes sign from positive to negative at \(c.\)

- \(f\) has no relative extremum at \(c\) if \(f'\) does not change sign at \(c.\)

- If \(f'(c) = 0\) and \(f''(c) \gt 0,\) then \(f\) has a relative minimum at \(x = c.\)

- If \(f'(c) = 0\) and \(f''(c) \lt 0,\) then \(f\) has a relative maximum at \(x = c.\)

- If \(f'(c) = 0\) and \(f''(c) = 0\) or \(f''(c)\) does not exist, then the test is inconclusive.

- If \(a = 13\) and \(b = 1,\) then their product is \(P = 13.\)

- If \(a = 12\) and \(b = 2,\) then their product is \(P = 24.\)

- If \(a = 11\) and \(b = 3,\) then their product is \(P = 33.\)

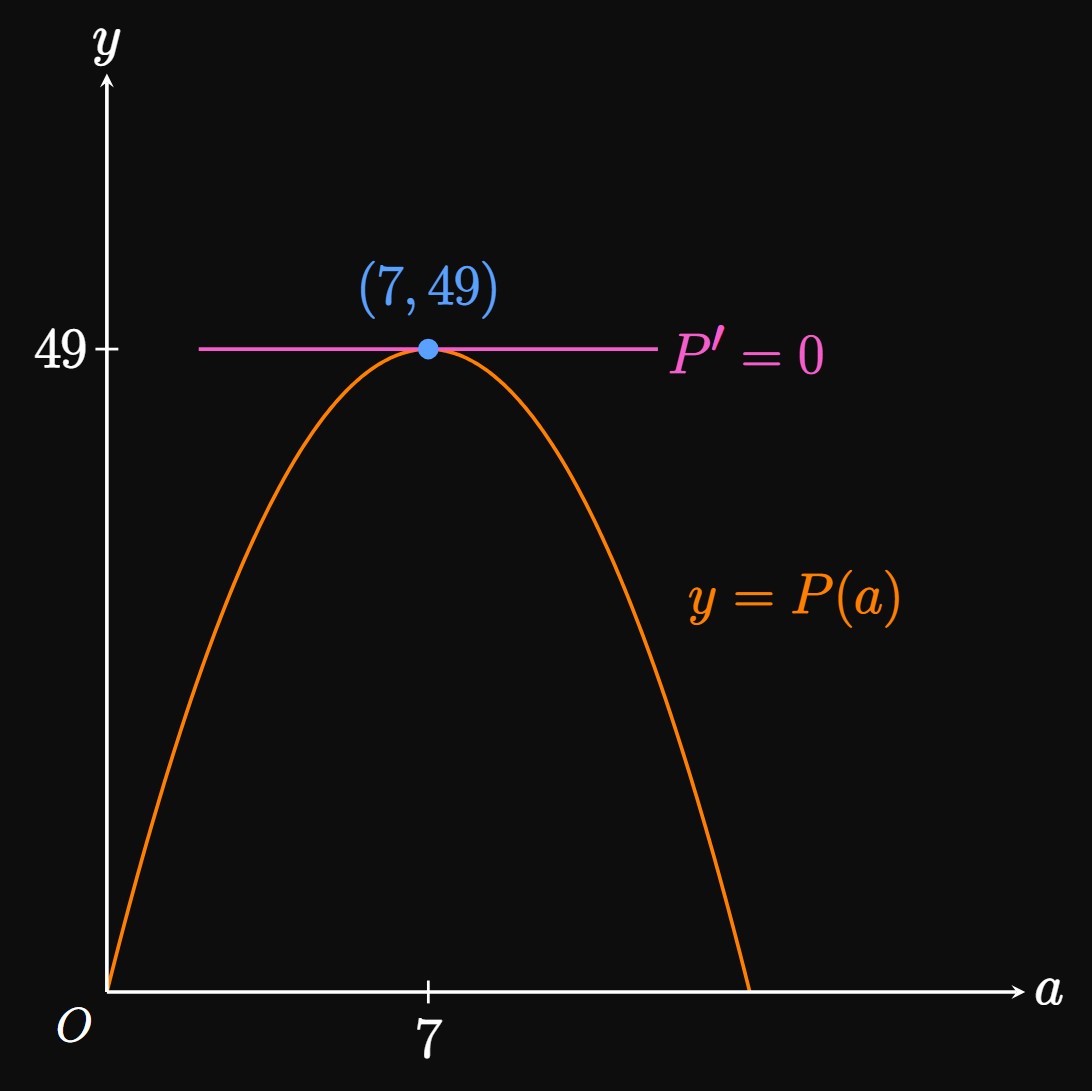

Optimization We find the critical numbers of \(P(a)\) by solving \(P'(a) = 0 \col\) \[ \ba P'(a) = 14 - 2a &= 0 \nl \implies a &= 7 \pd \ea \] For \(a \lt 7,\) \(P' \gt 0;\) for \(a \gt 7,\) \(P' \lt 0.\) Since \(P'(a)\) changes sign from positive to negative at \(a = 7,\) the First-Derivative Test states that \(a = 7\) is the location of a relative maximum of \(P.\) Also note the following:

- If \(a \lt 0,\) then \(b \gt 0\) and \(P \lt 0.\)

- If \(a \gt 14,\) then \(b \lt 0\) and \(P \lt 0.\)

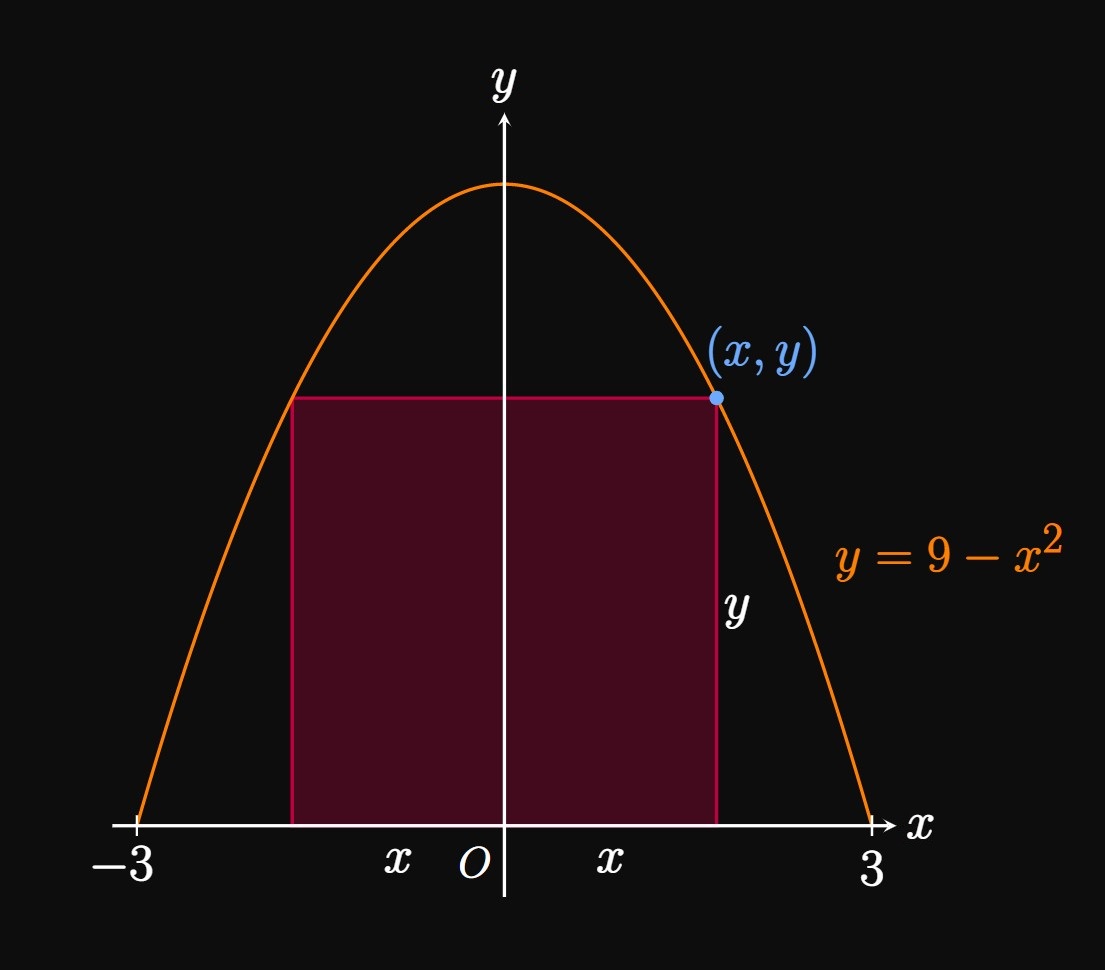

We create a sketch of the scenario (Figure 2). Let \(w\) denote the pen's width and \(\ell\) denote the pen's length. Also let \(A\) be the area of the pen. These suggestive variables help us avoid confusion. Let's construct a system of equations. The equation for the pen's perimeter is \begin{equation} 2w + \ell = 40 \pd \label{eq:farmer-1} \end{equation} We want to maximize \begin{equation} A = w \ell\ \pd \label{eq:farmer-2} \end{equation} Rearranging \(\eqref{eq:farmer-1}\) yields \(\ell = 40 - 2w,\) which we substitute into \(\eqref{eq:farmer-2}\) to acquire \[ A(w) = w \ell = w(40 - 2w) \pd\]

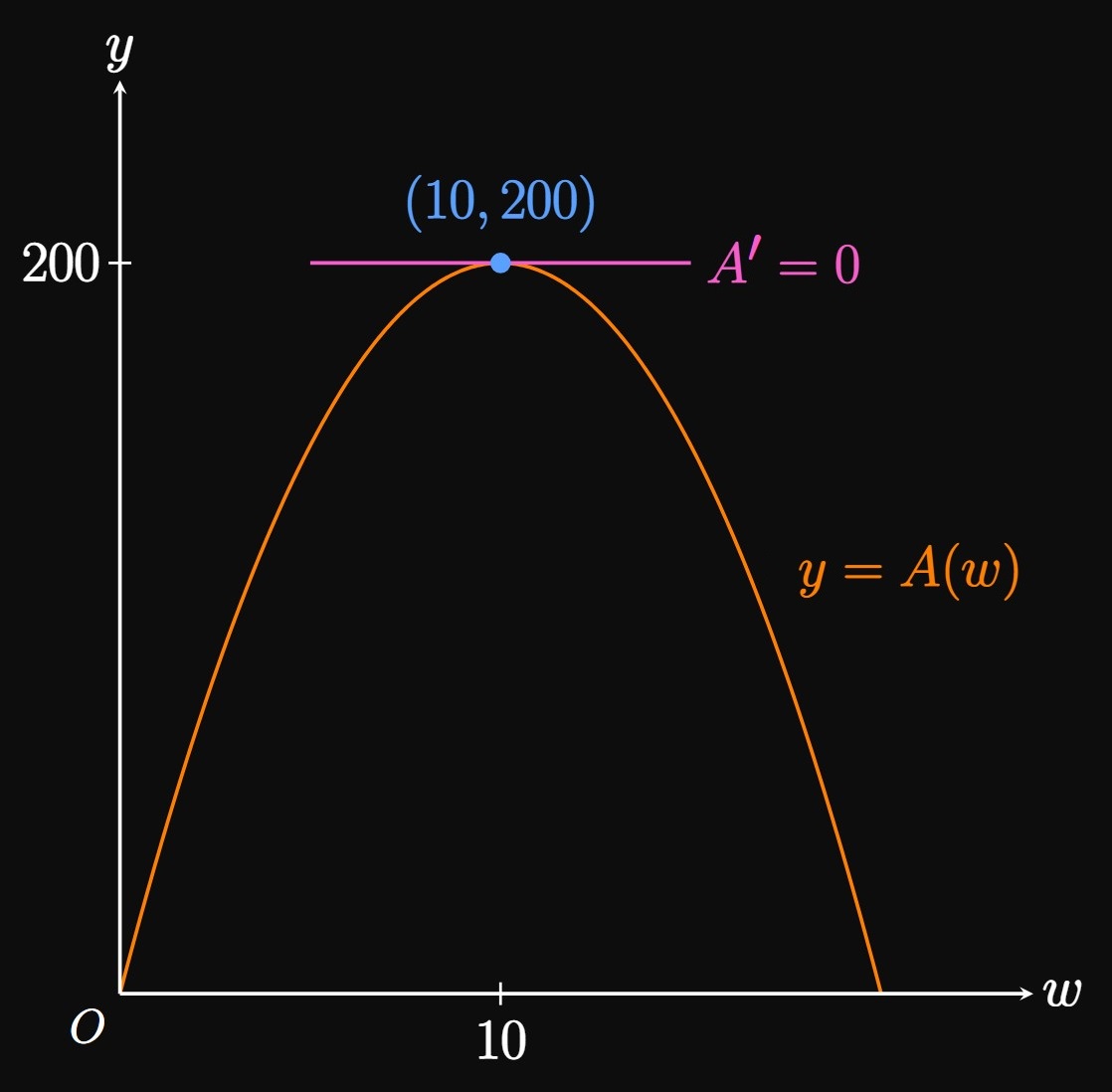

Optimization We differentiate \(A(w)\) and equate the result to \(0,\) seeing \[ \ba A'(w) = 40 - 4w &= 0 \nl \implies w &= 10 \pd \ea \] The domain in context is \(\{w \mid 0 \leq w \leq 20\};\) otherwise, side lengths become negative. The absolute maximum of \(A\) lies either at the endpoints of \(0 \leq w \leq 20\) or at its critical numbers. By the First-Derivative Test, \(w = 10\) corresponds to a relative maximum of \(A\) since \(A'(w)\) switches sign from positive to negative at \(w = 10.\) At \(w = 0\) and \(w = 20,\) \(A = 0\) because the pen collapses into a line. Thus, \(w = 10\) corresponds to the absolute maximum of \(A\) (Figure 3). For \(w = 10,\) we have \(\ell = 40 - 2(10) = 20.\) Thus, a pen of dimensions \(20\) feet by \(10\) feet produces the maximum area, \(200\) square feet.

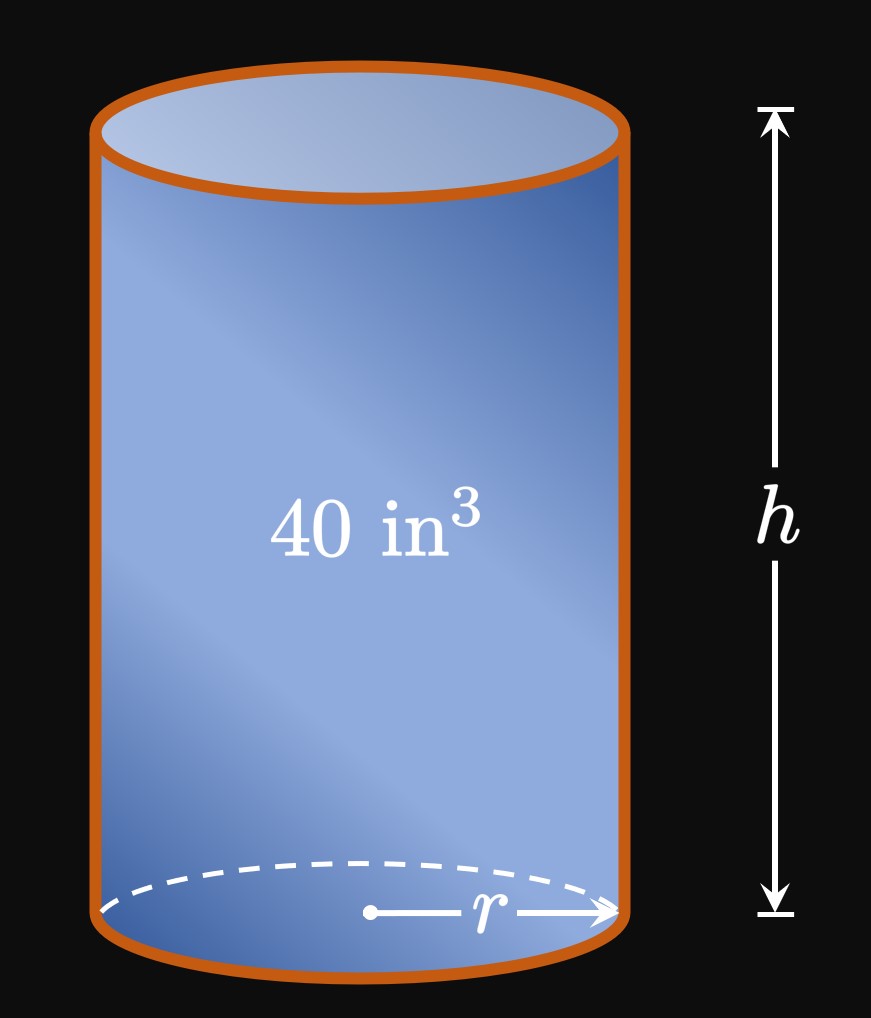

To understand the problem, we construct a picture (Figure 4). Let \(r\) be the can's radius and \(h\) be its height. The volume of the cylinder is then \begin{equation} 40 = \pi r^2 h \pd \label{eq:equation-cylinder-volume} \end{equation} We want to minimize the surface area: \begin{equation} S = 2 \pi r^2 + 2 \pi r h \pd \label{eq:equation-cylinder-SA} \end{equation} (To remember this formula, see that the bases of the can are circles of area \(\pi r^2,\) and a rectangular sheet of area \(2 \pi r h\) is wrapped around the can.) We aim to express \(S\) in terms of one variable. From \(\eqref{eq:equation-cylinder-volume},\) we have \(h = 40/(\pi r^2),\) which we substitute into \(\eqref{eq:equation-cylinder-SA}\) to get \[ \ba S(r) &= 2 \pi r^2 + 2 \pi r \left(\frac{40}{\pi r^2}\right) \nl &= 2 \pi r^2 + \frac{80}{r} \pd \ea \]

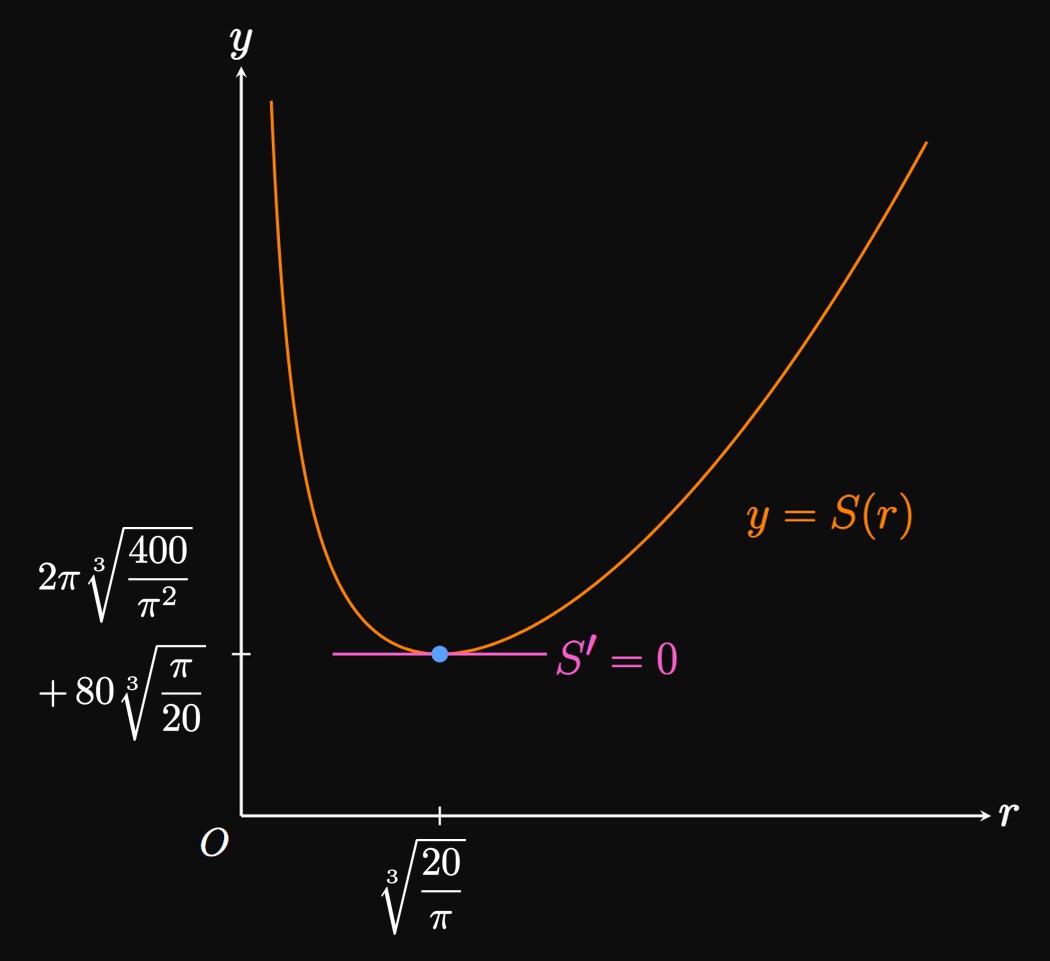

Optimization Differentiating \(S(r)\) gives \[S'(r) = 4 \pi r - \frac{80}{r^2} \pd\] To determine the critical numbers, we solve \(S'(r) = 0,\) as follows: \[ \ba S'(r) = 4 \pi r - \frac{80}{r^2} &= 0 \nl \implies r &= \sqrt[3]{\frac{20}{\pi}} \pd \nl \ea \] For \(r \lt \sqrt[3]{20/\pi},\) \(S' \lt 0;\) for \(r \gt \sqrt[3]{20/\pi},\) \(S' \gt 0.\) Since \(S'\) changes sign from negative to positive at \(r = \sqrt[3]{20/\pi},\) this value corresponds to a relative minimum of \(S\) by the First-Derivative Test. Also, because \(\lim_{r \to 0^+} S(r) = \infty\) and \(\lim_{r \to \infty} S(r) = \infty,\) there needs to be a minimum value of \(S(r),\) which must exist at the critical number (Figure 5). So \(r = \sqrt[3]{20/\pi}\) corresponds to the absolute minimum of \(S.\) We then have \(r \approx 1.853 \un{in}\) and \[h = \frac{40}{\pi (20/\pi)^{2/3}} \approx 3.707 \un{in} \pd\] Thus, a can of radius \(1.853 \un{in}\) and height \(3.707 \un{in}\) minimizes the materials used while holding the required volume. With a radius of \(1.853 \un{in},\) the cylinder's diameter is \(3.707 \un{in}\)—the same dimension as the height. The minimized surface area is \[ \ba S \par{\sqrt[3]{\frac{20}{\pi}}} &= 2 \pi \par{\sqrt[3]{\frac{20}{\pi}}}^2 + \frac{80}{\sqrt[3]{20/\pi}} \nl &= 2 \pi \sqrt[3]{\frac{400}{\pi^2}} + 80 \sqrt[3]{\frac{\pi}{20}} \nl &\approx 64.747 \un{in}^2 \pd \ea \]

If \(f(x)\) has a relative minimum or maximum at \(x = a,\) then so does \(\sqrt{f(x)}.\) For example, \[p(x) = \sqrt{3 + (x - 2)^2} \and q(x) = 3 + (x - 2)^2\] each have a relative minimum at \(x = 2.\) This fact is convenient because we can choose to optimize the square of a function—often an easier process.

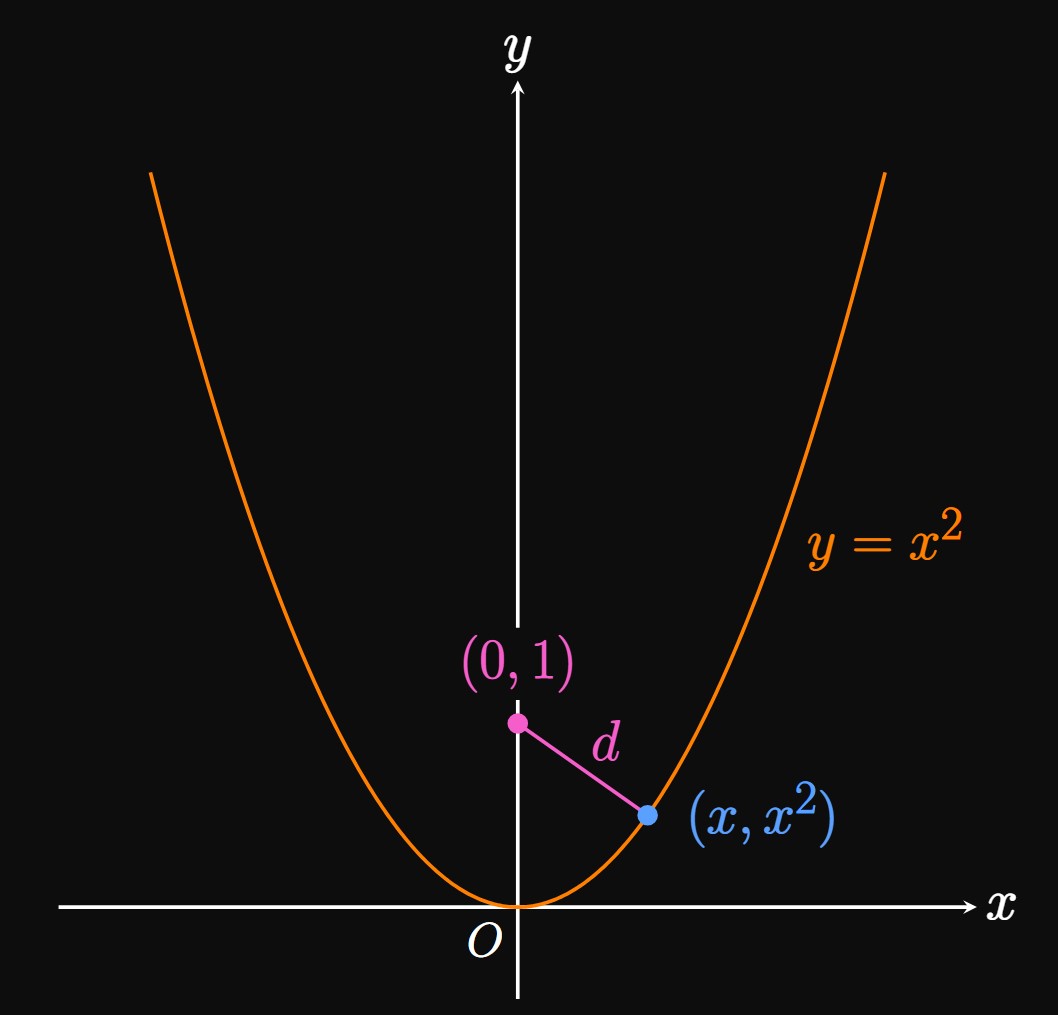

Figure 6 shows a sketch of the parabola and the points \((0, 1)\) and \((x, y)\) \(= (x, x^2).\) The distance between the points is, by the Distance Formula, \[ \ba d &= \sqrt{(x - 0)^2 + (y - 1)^2} \nl &= \sqrt{(x - 0)^2 + (x^2 - 1)^2} \nl &= \sqrt{x^4 - x^2 + 1} \pd \ea \]

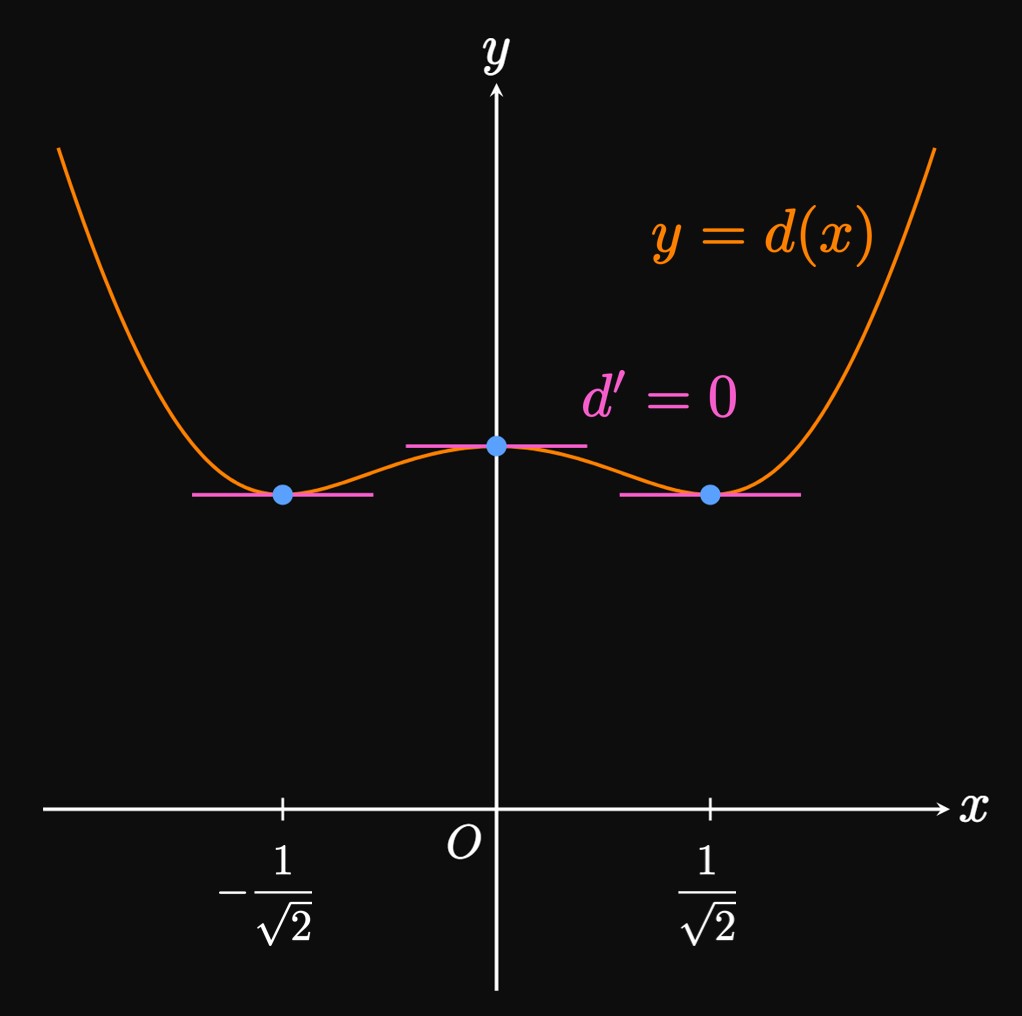

Optimization We need to find the critical numbers of \(d.\) But \(d^2\) has the same critical numbers, so we choose to optimize \(d^2\) for convenience: Let \(q(x) = d^2\) \(= x^4 - x^2 + 1,\) whose derivative is \[q'(x) = 4x^3 - 2x \pd\] Solving \(q'(x) = 0,\) we find \[ \ba 4x^3 - 2x &= 0 \nl 2x(2x^2 - 1) &= 0 \nl \implies x &= 0 \cma \frac{-1}{\sqrt 2} \cma \frac{1}{\sqrt 2} \pd \ea \]

Note that \(q'\) changes sign from positive to negative at \(x = 0,\) so this value corresponds to a relative maximum of \(q\) by the First-Derivative Test. But we seek to minimize \(q,\) so we ignore this critical number. Conversely, \(q'\) changes sign from negative to positive at both \(x = -1/\sqrt 2\) and \(x = 1/\sqrt 2.\) So both values are locations of relative minima of \(q.\) Because \[\lim_{x \to -\infty} q(x) = \infty \and \lim_{x \to \infty} q(x) = \infty \cma\] the absolute minima of \(q\)—and therefore the absolute minima of \(d\)—must occur when \(x = -1/\sqrt 2\) and \(x = 1/\sqrt 2\) (Figure 7). At each value, \(y = (\pm 1/\sqrt 2)^2\) \(= 1/2.\) Thus, the closest points on the parabola to \((0, 1)\) are \[\boxed{\par{\frac{-1}{\sqrt 2} \cma \frac{1}{2}}} \and \boxed{\par{\frac{1}{\sqrt 2} \cma \frac{1}{2}}}\] as we expect from the parabola's symmetry.

REMARK If we differentiated \(d,\) then we would've gotten \[d'(x) = \frac{4x^3 - 2x}{\sqrt{x^4 - x^2 + 1}} \cma\] which has the same zeros as \(q'(x),\) confirming that \(d\) and \(q(x) = d^2\) have the same critical numbers.

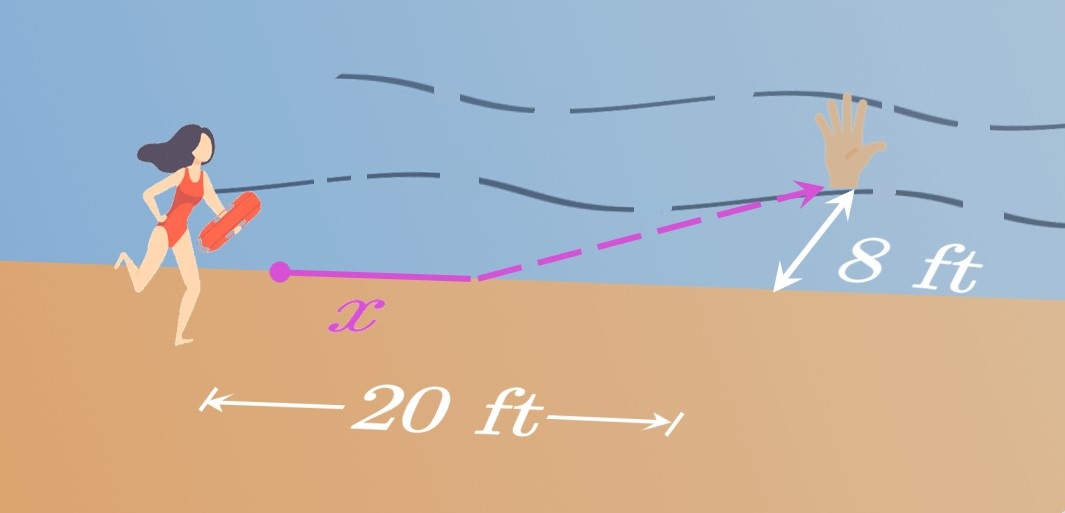

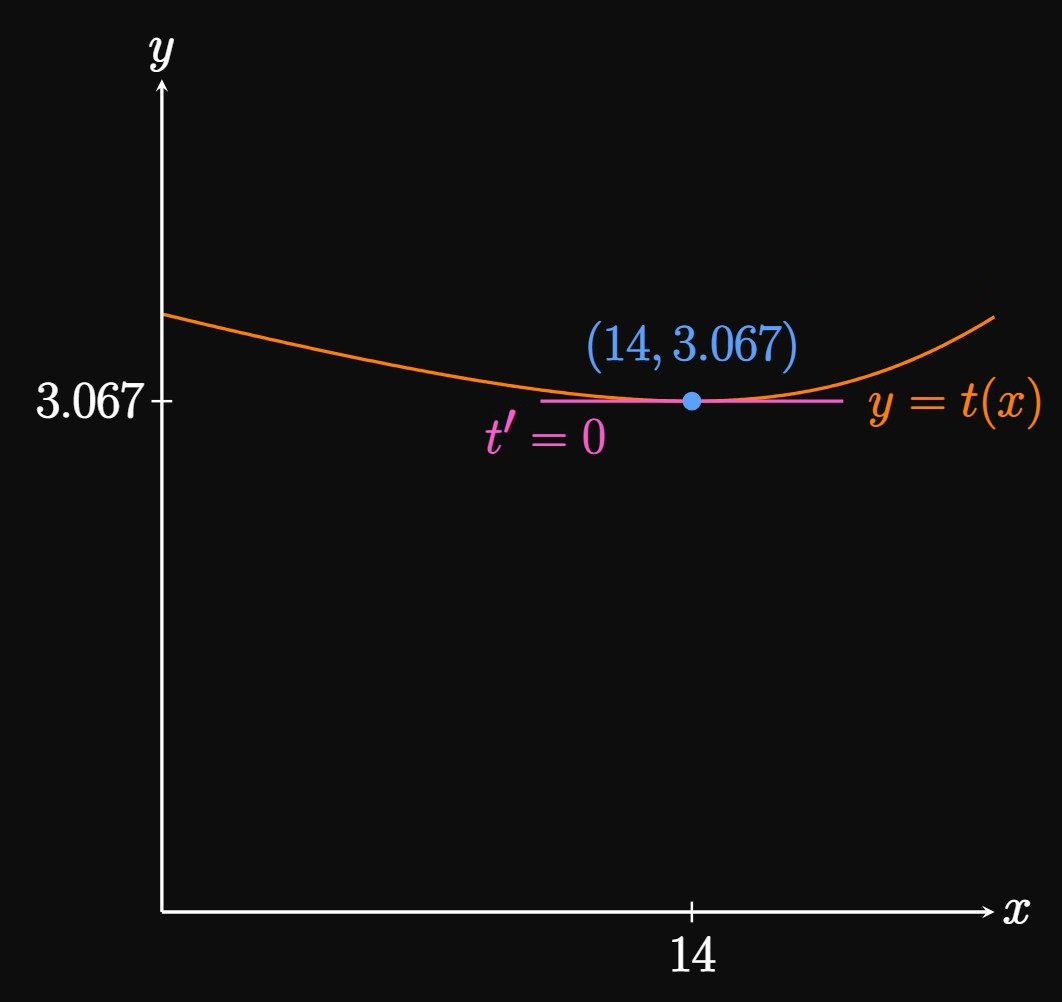

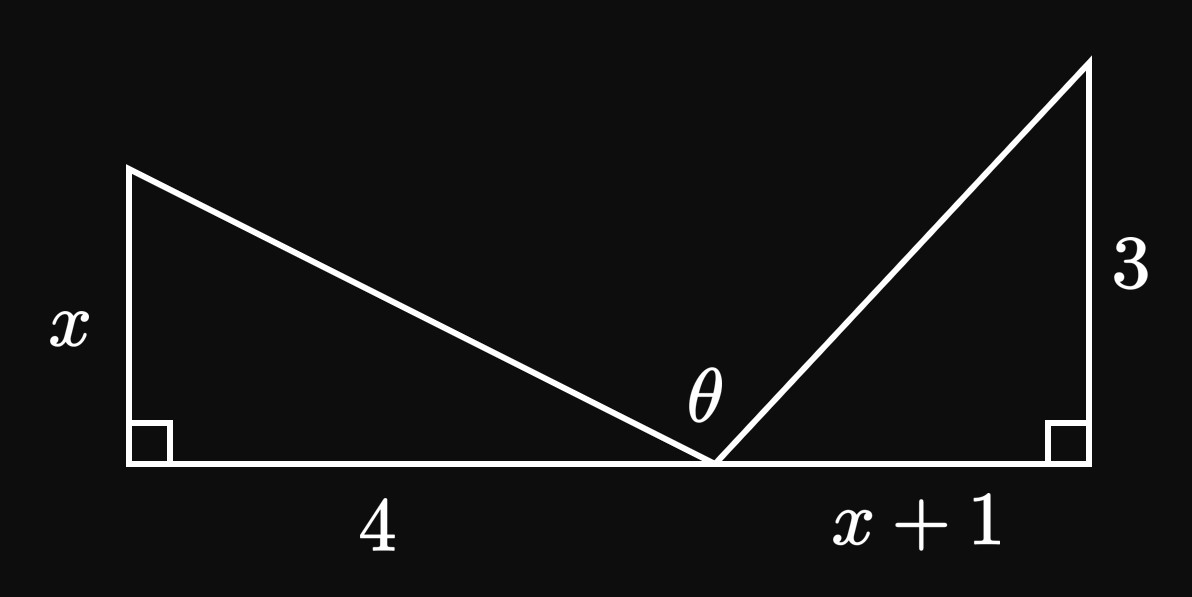

Optimization Differentiating with respect to \(x\) shows \[ t'(x) = \frac{1}{10} + \frac{x - 20}{6 \sqrt{x^2 - 40x + 464}} \pd \] To locate the critical numbers of \(t,\) we solve \(t'(x) = 0,\) as follows: \[ \ba \frac{1}{10} + \frac{x - 20}{6 \sqrt{x^2 - 40x + 464}} &= 0 \nl \frac{6 \sqrt{x^2 - 40x + 464} + 10 x - 200}{60 \sqrt{x^2 - 40x + 464}} &= 0 \nl 6 \sqrt{x^2 - 40x + 464} + 10 x - 200 &= 0 \nl 6 \sqrt{x^2 - 40x + 464} &= -10x + 200 \nl 36 \par{x^2 - 40x + 464} &= 100x^2 - 4000x + 40000 \nl 64 (x - 26)(x - 14) &= 0 \nl \implies x &= 14 \cma 26 \pd \ea \] The domain of \(t(x)\) in context is \(\{x \mid 0 \leq x \leq 20\},\) so the solution \(x = 26\) is extraneous. Observe that \(t' \lt 0\) for \(0 \leq x \lt 14\) and \(t' \gt 0\) for \(14 \lt x \leq 20.\) Hence, \(t\) has a relative minimum at \(x = 14\) by the First-Derivative Test. Note that \(t(0) \approx 3.590,\) \(t(14) \approx 3.067,\) and \(t(20) \approx 3.333.\) Consequently, \(t\) has an absolute minimum at \(x = 14\) (Figure 10). So the lifeguard should run \(\boxed{14 \un{ft}}\) before jumping in the water to save the swimmer in just \(3.067\) seconds.

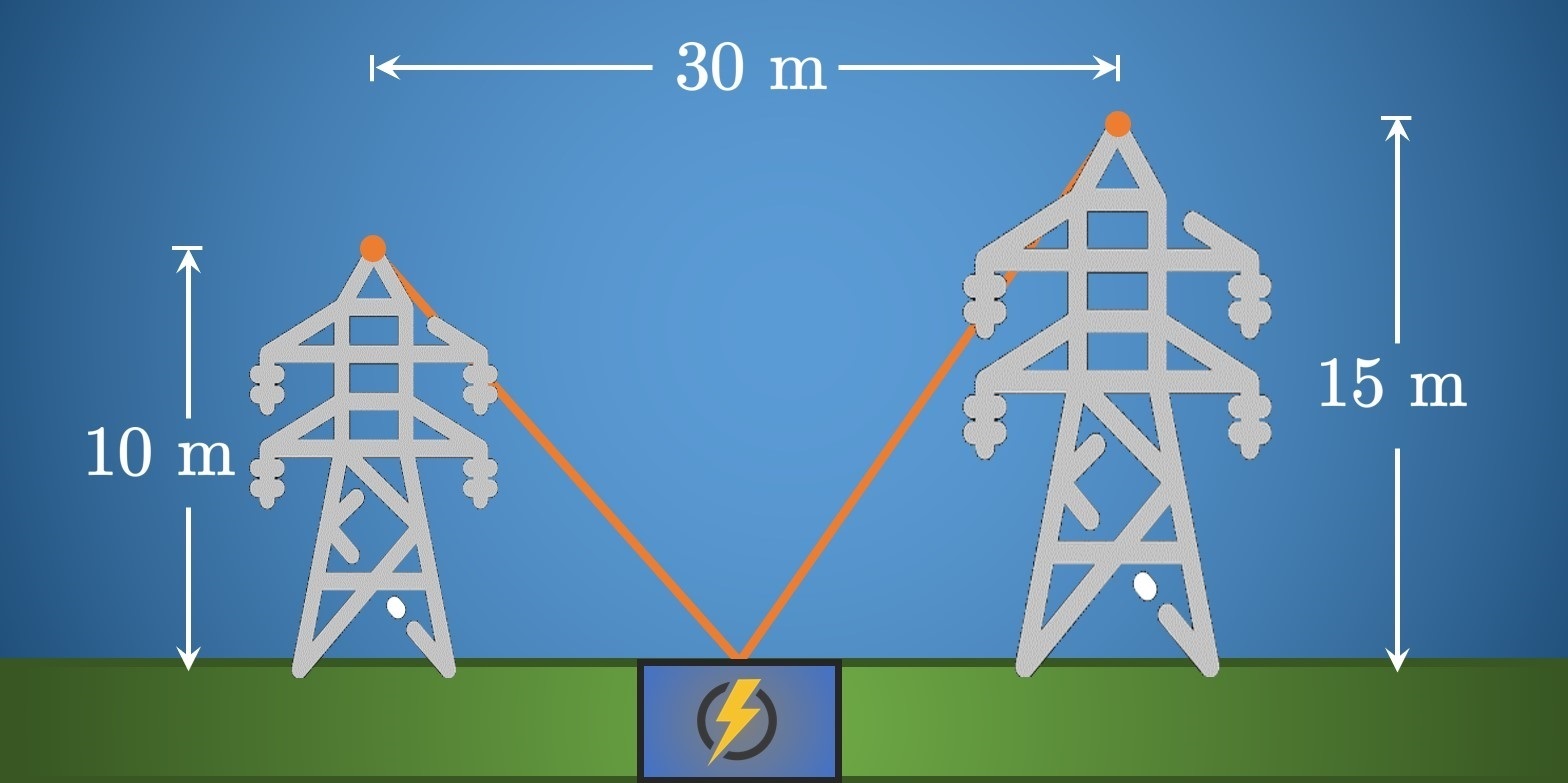

Optimization Differentiating \(w\) to locate its critical points, we see \[ \ba \frac{\dd w}{\dd x} = \frac{x}{\sqrt{x^2 + 100}} + \frac{x - 30}{\sqrt{x^2 - 60x + 1125}} &= 0 \nl \implies x &= 12 \pd \ea \] By graphing \(y = w(x),\) you may convince yourself that this critical number is the location of the absolute minimum of \(w.\) Thus, the optimal spot to anchor the wires is \(\boxed{12 \un{m}}\) to the right of the left tower.

Optimization is the procedure of minimizing or maximizing a quantity. When solving word problems, it is crucial to read carefully and sketch a diagram. The following tips guide you through the process of optimization:

- Understand Understand the situation by drawing diagrams and testing various possibilities.

- Notation Assign a variable—say, \(Q\)—to the quantity to maximize or minimize. Introduce notation by assigning algebraic quantities to unknown values. It is helpful to use suggestive variables, such as \(A\) for area, \(d\) for distance, and \(L\) for length.

- Express Express \(Q\) in terms of one variable—say, \(x\)—to obtain \(Q(x).\)

- Minimize or Maximize Use calculus to find the absolute minimum or maximum of \(Q(x).\) Find the critical numbers of \(Q\) and consider the endpoints of the domain in context.